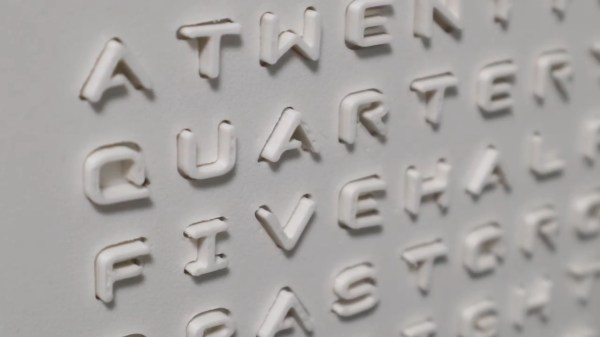

The versatility of 3D printers is simply amazing. Capable of producing a wide variety of prototypes, miscellaneous parts, artwork, and even other 3D printers, it’s an excellent addition to any shop or makerspace. The smaller, more inexpensive printers might do one type of printing well with a single tool, but if you really want to take a 3D printer’s versatility up to the next level you may want to try one with an automatic tool changing system like this one which uses magnets.

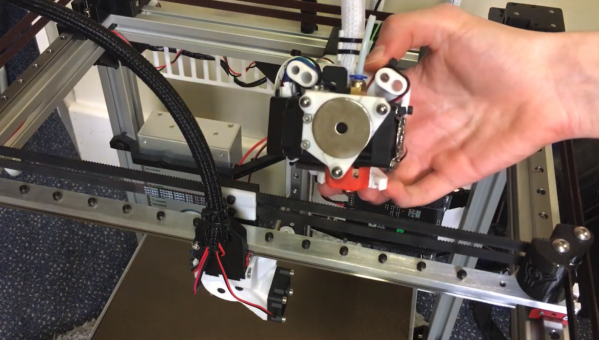

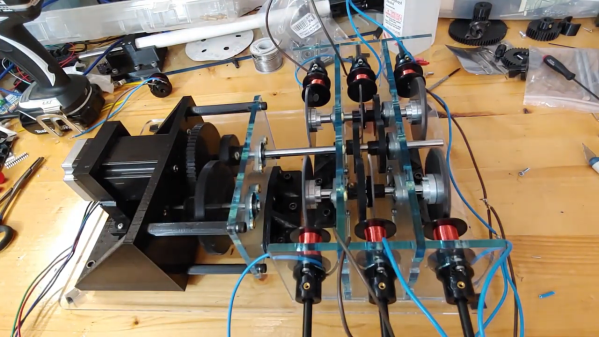

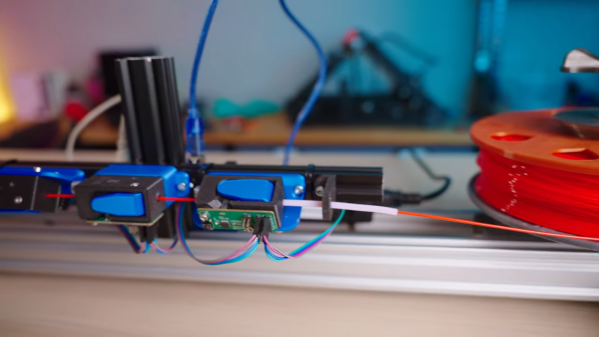

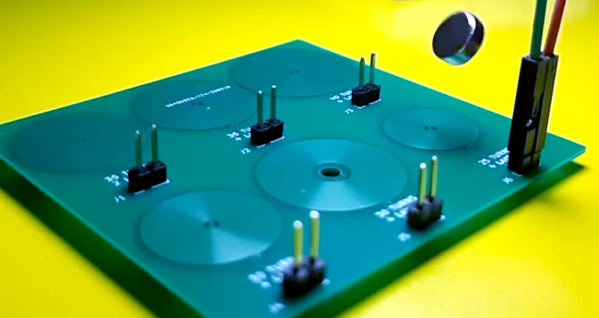

This 3D printer from [Will Hardy] uses an electromagnet to attach the tool to the printer. The arm is able to move to the tool storage area and quickly deposit and attach various tools as it runs through the prints. A failsafe mechanism keeps the tool from falling off of the head of the printer in case of a power outage, and several other design features were included to allow others to tweak this design to their own particular needs, such as enclosing the printer and increasing or decreasing the working area of the Core-XY printer as needed.

While the project looks like it works exceptionally well, [Will] notes that it is still in the prototyping phase and needs work on the software in order to refine its operation and make it suitable for more general-purpose uses. It’s an excellent design though and shows promise. It also reminds us of this other tool-changing system we featured a few months ago, albeit with a less electromagnetic twist.

Continue reading “A 3D Printer With An Electromagnetic Tool Changer”