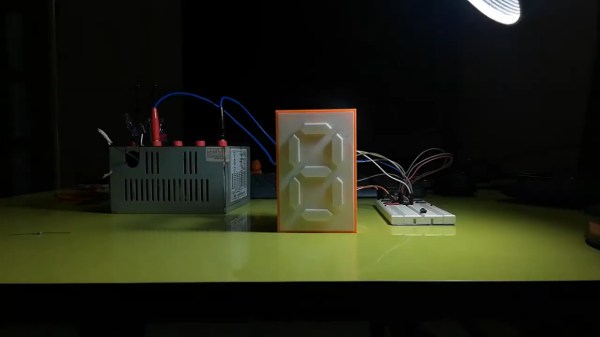

We’ve been displaying numbers using segmented displays for almost 120 years now, an invention that predates the LEDs that usually power the ubiquitous devices by a half-dozen decades or so. But LEDs are far from the only way to run a seven-segment display — check out this mechanical seven-segment display for proof of that.

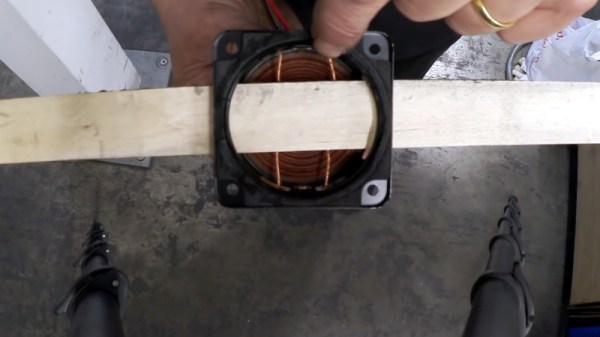

We’ve been seeing a lot of mechanical seven-segment displays lately, and when we first spotted [indoorgeek]’s build, we thought it would be a variation on the common “flip-dot” mechanism. But this one is different; to form each numeral, the necessary segments protrude from the face of the display slightly. Everything is 3D-printed from white filament, yielding a clean look when the retracted but casting a sharp shadow when extended. Each segment carries a small magnet on the back which snuggles up against the steel core of a custom-wound electromagnet, which repels the magnet when energized and extends the segment. We thought for sure it would be loud, but the video below shows that it’s really quiet.

While we like the subtle contrast of the display, it might not be enough for some users, especially where side-lighting is impractical. In that case, they might want to look at this earlier similar display and try contrasting colors on the sides of each segment.

Continue reading “Mechanical Seven-Segment Display Really Sticks Out From The Pack”