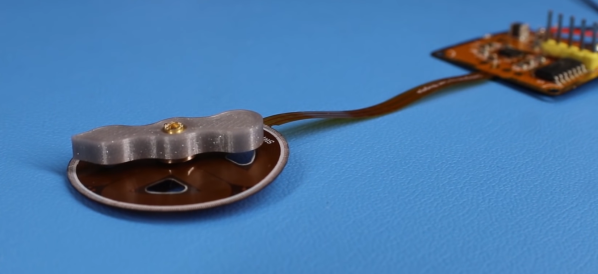

The [Denki Otaku] YouTube channel took a look recently at some stepper motors, or ‘stepping motors’ as they’re called in Japanese. Using a 2-phase stepper motor as an example, the stepper motor is taken apart and its components explained. Next a primer on the types and the ways of driving stepper motors is given, providing a decent overview of the basics at the hand of practical examples.

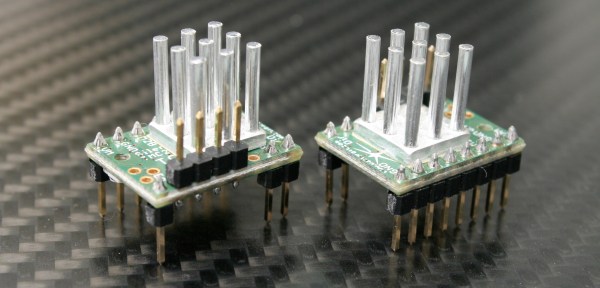

As great as theoretical explanations are, there’s a lot of value in watching the internals of a stepper motor move when its coils are activated in order. Also demonstrated are PWM-controlled stepper motor drivers before diving into the peculiarities of microstepping, whereby the driving of the coils is done such that the stator moves in the smallest possible increments, often through flux levels in these coils. This allows for significantly finer positioning of the output shaft than with wave stepping and similar methods that are highly dependent on the number of phases and coils.

As demonstrated in the video, another major benefit of microstepping is that it creates much smoother movement while moving, but also noted is that servo motors are often what you want instead. This is a topic which we addressed in our recent article on the workings of stepper motors, with particular focus on the 4-phase 28BYJ-48 stepper motor and the disadvantages of steppers versus servos.

Continue reading “Stepper Motor Operating Principle And Microstepping Explained”