What’s the weirdest computer you can think of? This one’s weirder.

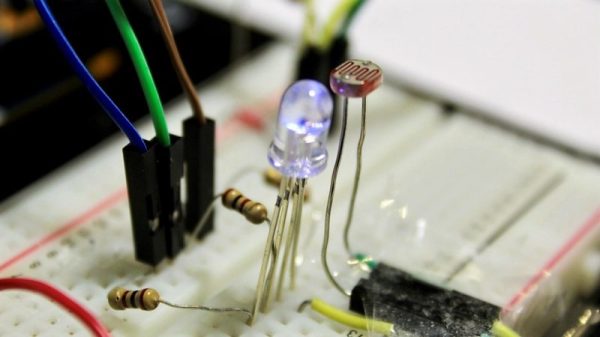

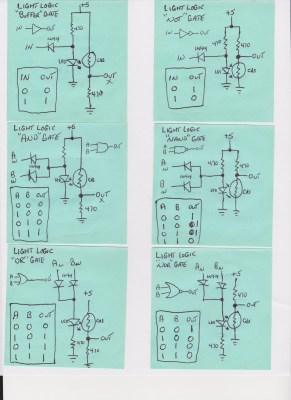

[Dr. Cockroach] figured out a way to create an inverting NOT gate from just one LED and two resistors (one being a photo-resistor). The Dr. has since built AND, NAND, OR, NOR, XOR and XNOR gates, as well as a buffer, incorporating light into every logic gate.

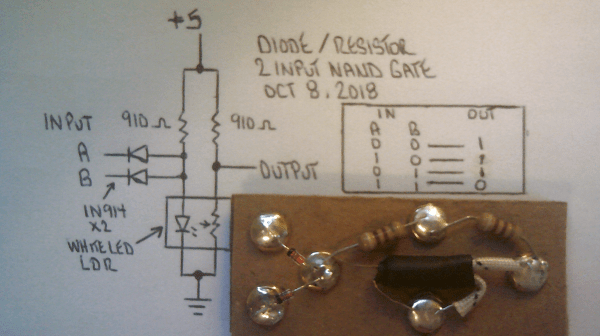

Traditional inverters – NOT gates – are already made with diodes (typically not light-emitting), resistors (typically not light-dependent), and bipolar transistors. The challenge was to reduce the number of transistors. The schematic from the very first test shows the slight modifications [Dr. Cockroach] made to incorporate light into the logic gate using a 910 Ohm, output LED, and an LED and LDR in parallel.

The output is initially 4.5V for logic 1 and 1.5V for logic 0. Adding two 1N914 diodes and an AND gate ahead of the inverter create a two-input NAND gate. With the two diodes reversed and a 910 Ohm resistor removed, a NOR gate is created.

The next step was to build a S-R latch using the NAND gates and inverters, which holds some basic memory. From there, with some size reductions, a Master-Slave J-K Flip Flop, similarly using NAND gates and inverters, can be built. The current state of the project is a working sequencer and counter. You can even see a smooth sine wave propagating through the LED chaser, which is typically built with ICs or transistors but in this case is built simply with LEDs, LDRs, resistors, and capacitors.

The upcoming plan is to use the gates to build a processor that only uses diodes, resistors, and capacitors. While it’s probably not going to be nearly as fast as any processors we have today, it should be interesting (and educational!) to be able to visually track the flow of data from one logic gate over to the next. Continue reading “Light Emitting Logic Gates Built From Scratch”

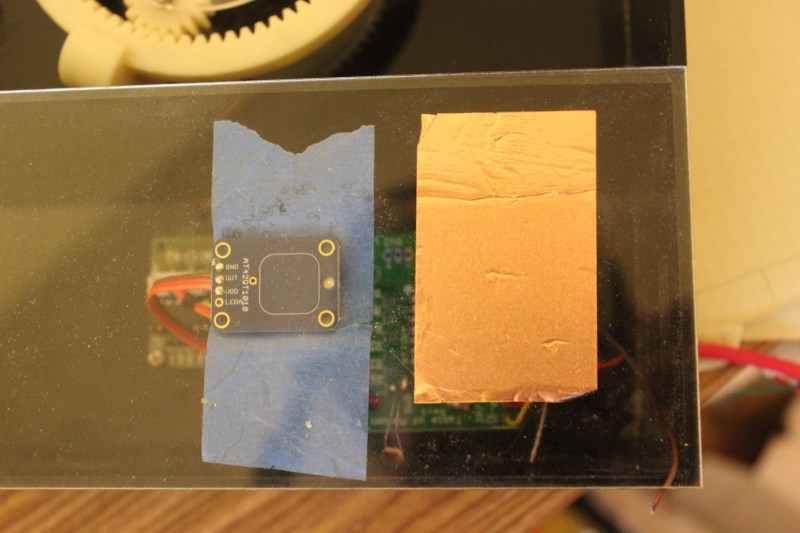

A flashing LCD screen and a photo-resistor barely make the cut for a one-way LiFi system, but [Eduardo Zola] makes it work. The approach is to build a resitor divider and watch an input pin on the ESP for changes.

A flashing LCD screen and a photo-resistor barely make the cut for a one-way LiFi system, but [Eduardo Zola] makes it work. The approach is to build a resitor divider and watch an input pin on the ESP for changes.