Join us on Wednesday, August 11 at noon Pacific for the Vintage Displays Hack Chat with Fran Blanche!

In terms of ease of integration and density of the information that can be shown, it’s hard to argue with the fact that modern displays like LCD panels are anything but superior to the character-based displays of yore. Throw one into a project, add a little code from a few off-the-shelf libraries to drive it, and you’re on to the next job.

Efficient, yes, but what does this approach do for the engineer’s soul? What design itch does it scratch; what aesthetic does it celebrate? Nostalgic questions, true, and not every project lends itself to exploring old display technologies. But some still do, thankfully, and when the occasion calls for it, we’re glad that there are those out there who are still actively involved in the retro display community, making sure that what was once state-of-the-art technology is still able to be added to modern projects.

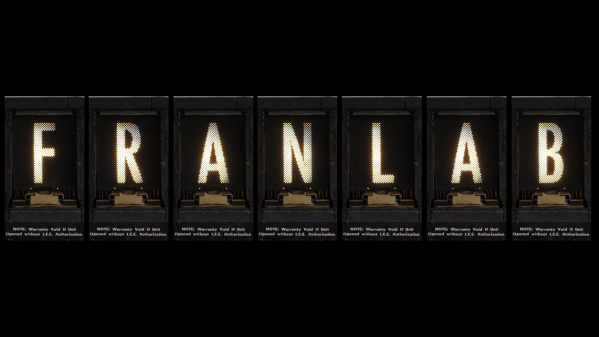

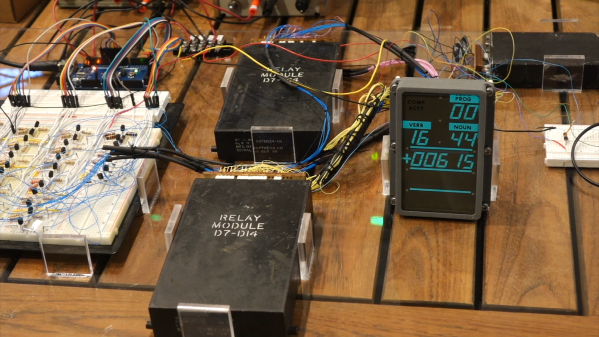

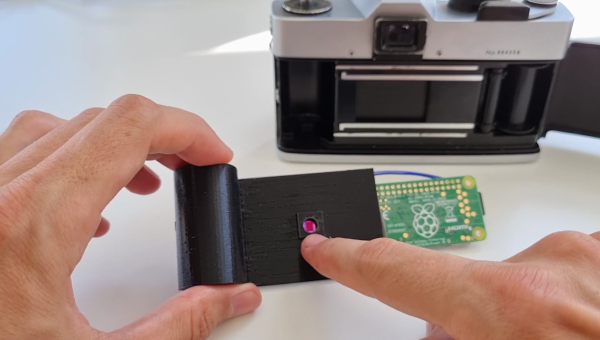

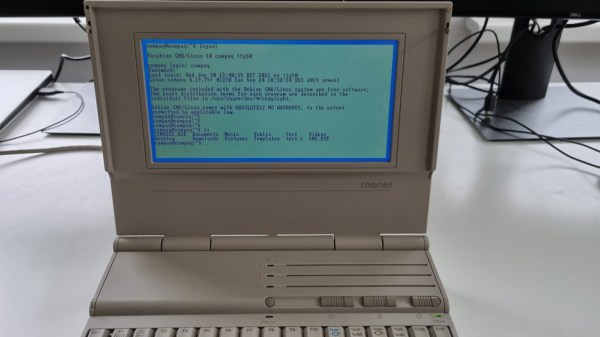

There’s no doubt that Fran Blanche is one of those passing the torch of vintage displays down to the next generation. You’ll certainly know Fran from her popular Fran Lab channel on YouTube, where in addition to about a million other interests, she has explored some really cool vintage displays: the Nimo cathode-ray tube, super-bright incandescent seven-segment displays, the delightfully strange “Bina-View”, and many, many more. Fran will stop by the Hack Chat to talk about all these retro displays, what she’s learned from collecting them, and how they shaped the displays we take so much for granted these days. Oh, and perhaps we’ll also talk about her upcoming ride on “G-Force 1” as well.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, August 11 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, August 11 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.