Readers who were firmly on Team Nintendo in the early 2000’s or so can tell you that there was no accessory cooler for the Nintendo GameCube than the WaveBird. Previous attempts at wireless game controllers had generally either been sketchy third-party accessories or based around IR, and in both cases the end result was that the thing barely worked. The WaveBird on the other hand was not only an official product by Nintendo, but used 2.4 GHz to communicate with the system. Some concessions had to be made with the WaveBird; it lacked rumble, was a bit heavier than the stock controllers, and required a receiver “dongle”, but on the whole the WaveBird represented the shape of things to come for game controllers.

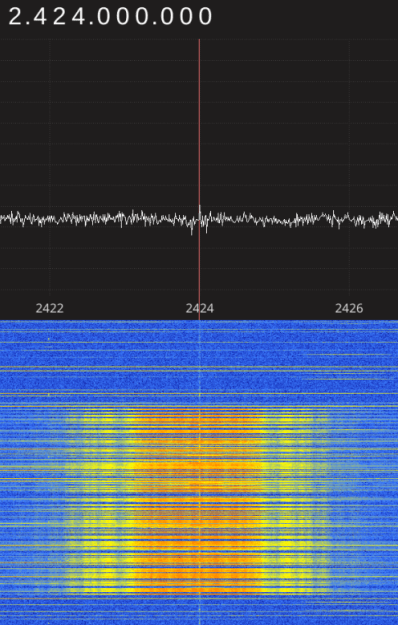

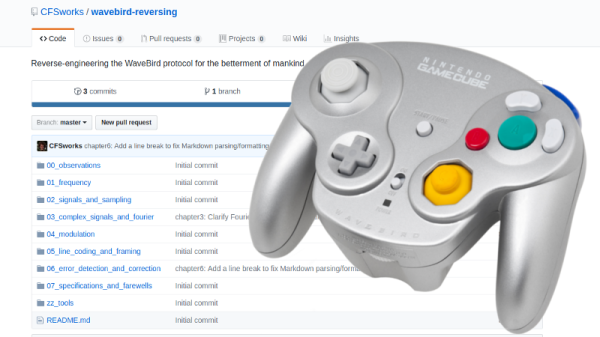

Given the immense popularity of the WaveBird, [Sam Edwards] was somewhat surprised to find very little information on how the controller actually worked. Looking for a project he could use his HackRF on, [Sam] decided to see if he could figure out how his beloved WaveBird communicated with the GameCube. This moment of curiosity on his part spawned an awesome 8 part series of guides that show the step by step process he used to unlock the wireless protocol of this venerable controller.

Even if you’ve never seen a GameCube or its somewhat pudgy wireless controller, you’re going to want to read though the incredible amount of information [Sam] has compiled in his GitHub repository for this project.

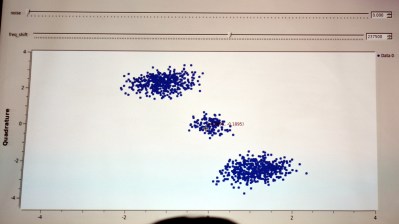

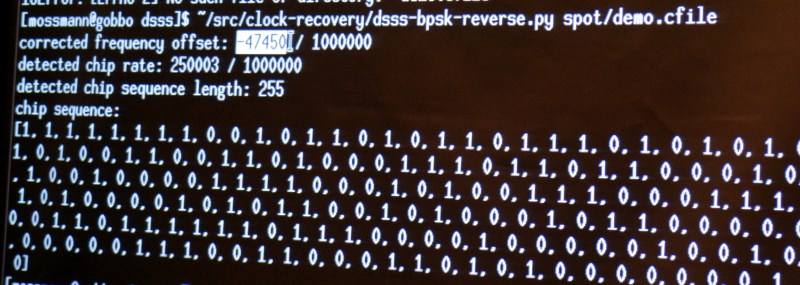

Starting with defining what a signal is to begin with, [Sam] walks the reader though Fourier transforms, the different types of modulations, decoding packets, and making sense of error correction. In the end, [Sam] presents a final summation of the wireless protocol, as well as a simple Python tool that let’s the HackRF impersonate a WaveBird and send button presses and stick inputs to an unmodified GameCube.

This amount of work is usually reserved for those looking to create their own controllers from the ground up, so we appreciate the effort [Sam] has gone through to come up with something that can be used on stock hardware. His research could have very interesting applications in the world of “tool-assisted speedruns” or even automating mindless stat-grinding.

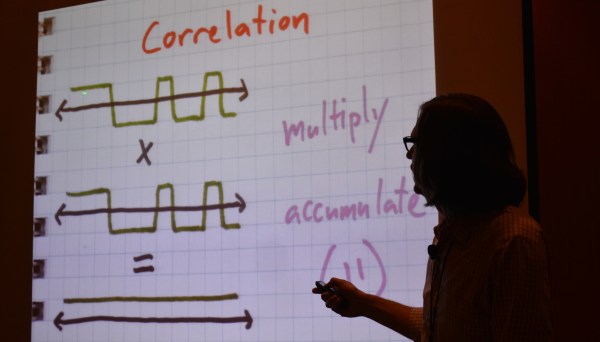

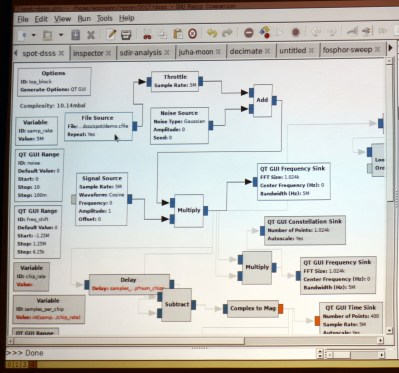

[Michael] mentioned simple math tricks, and he wasn’t kidding. It’s easy to assume that someone as experienced in RF as he would have a different definition of ‘simple’ than we would. But truly, he’s using multiplication and subtraction to do an awful lot.

[Michael] mentioned simple math tricks, and he wasn’t kidding. It’s easy to assume that someone as experienced in RF as he would have a different definition of ‘simple’ than we would. But truly, he’s using multiplication and subtraction to do an awful lot.