Stand up right now and walk around for a minute. We’re pretty sure you didn’t see everywhere you stepped nor did you plan each step meticulously according to visual input. So why should robots do the same? Wouldn’t your robot be more versatile if it could use its vision to plan a path, but leave most of the walking to the legs with the help of various sensors and knowledge of joint positions?

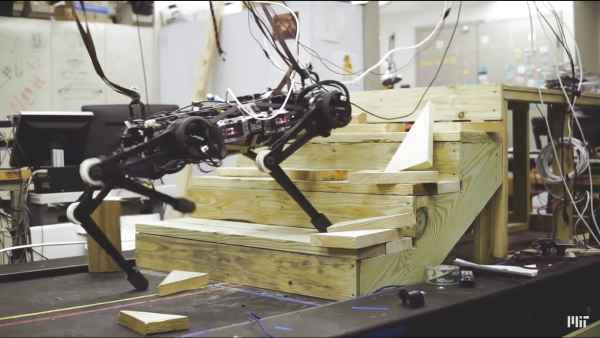

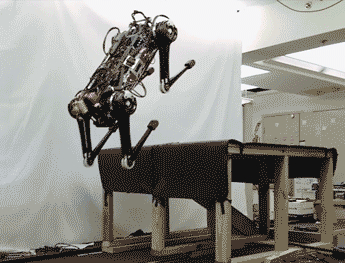

That’s the approach [Sangbae Kim] and a team of researchers at MIT are taking with their Cheetah 3. They’ve given it cameras but aren’t using them yet. Instead, they’re making sure it can move around blind first. So far they have it walking, running, jumping and even going up stairs cluttered with loose blocks and rolls of tape.

Two algorithms are at the heart of its being able to move around blind.

The first is a contact detection algorithm which decides if the legs should transition between a swing or a step based on knowledge of the joint positions and data from gyroscopes and accelerometers. If it tilted unexpectedly due to stepping on a loose block then this is the algorithm which decides what the legs should do.

The second is a model-predictive algorithm. This predicts what force a leg should apply once the decision has been made to take a step. It does this by calculating the multiplicative positions of the robot’s body and legs a half second into the future. These calculations are done 20 times a second. They’re what help it handle situations such as when someone shoves it or tugs it on a leash. The calculations enabled it to regain its balance or continue in the direction it was headed.

There are a number of other awesome features of this quadruped robot which we haven’t seen in others such as Boston Dynamics’ SpotMini like invertible knee joints and walking on three legs. Check out those features and more in the video below.

Of course, SpotMini has a whole set of neat features of its own. Let’s just say that while they look very similar, they’re on two different evolutionary paths. And the Cheetah certainly has evolved since we last looked at it a few years ago.

Continue reading “Cheetah 3 Is Learning To Move Blindly Before Learning To See”