Join us on Wednesday, March 17 at noon Pacific for the Retro Recreations Hack Chat with Tube Time!

Nostalgia seems to be an inevitable consequence of progress. Advance any field far enough into the future, and eventually someone will look back with misty eyes and fond memories of the good old days and start the process of turning what would qualify as junk under normal conditions into highly desirable collectibles.

Nostalgia seems to be an inevitable consequence of progress. Advance any field far enough into the future, and eventually someone will look back with misty eyes and fond memories of the good old days and start the process of turning what would qualify as junk under normal conditions into highly desirable collectibles.

In some ways, those who have been bitten by the computer nostalgia bug are lucky, since the sheer number of artifacts produced during their period of interest is likely to be pretty high, making getting gear to lovingly restore relatively easy. But even products produced in their millions can eventually get difficult to find, especially once they get snapped up by eager collectors, leaving the rest to make do or do without.

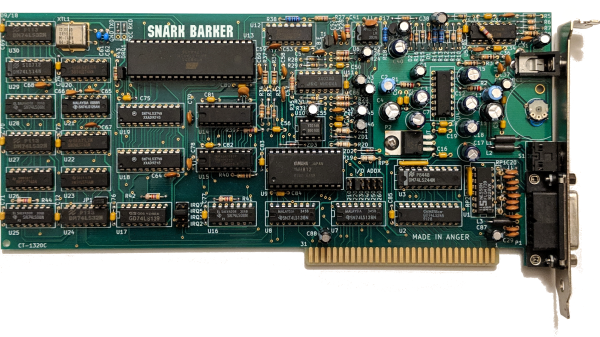

Of course, if you’re as resourceful as Tube Time is, there’s another alternative: build your own retro recreations. He has embarked on some pretty intense builds to recapture a little of what early computer enthusiasts went through trying to build useful machines. He has built replicas of early PC sound cards, like an ISA-bus AdLib card, its MCA equivalent, and the “Snark Barker”— or is it the “Snood Bloober”? — which bears an uncanny resemblance to the classic Sound Blaster card from the 1980s.

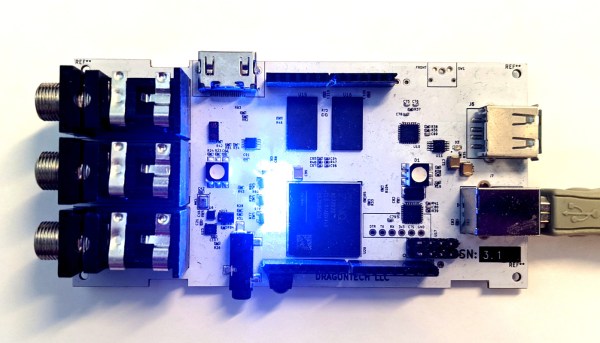

Tube Time will join us for the Hack Chat this week to answer questions about all his retro recreations, including his newest work on a retro video card. Be sure to bring your questions on retro rebuilds, reverse engineering, and general computer nostalgia to the chat.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, March 17 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.

Continue reading “Retro Recreations Hack Chat With Tube Time”