Before swearing my fealty to the Jolly Wrencher, I wrote for several other sites, creating more or less the same sort of content I do now. In fact, the topical overlap was enough that occasionally those articles would get picked up here on Hackaday. One of those articles, which graced the pages of this site a little more than seven years ago, was Getting Started with RTL-SDR. The original linked article has long since disappeared, and the site it was hosted on is now apparently dedicated to Nintendo games, but you can probably get the gist of what it was about from the title alone.

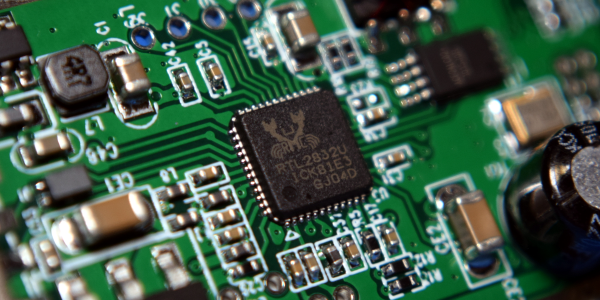

When I wrote that article in 2012, the RTL-SDR project and its community were still in their infancy. It took some real digging to find out which TV tuners based on the Realtek RTL2832U were supported, what adapters you needed to connect more capable antennas, and how to compile all the software necessary to get them listening outside of their advertised frequency range. It wasn’t exactly the most user-friendly experience, and when it was all said and done, you were left largely to your own devices. If you didn’t know how to create your own receivers in GNU Radio, there wasn’t a whole lot you could do other than eavesdrop on hams or tune into local FM broadcasts.

Nearly a decade later, things have changed dramatically. The RTL-SDR hardware and software has itself improved enormously, but perhaps more importantly, the success of the project has kicked off something of a revolution in the software defined radio (SDR) world. Prior to 2012, SDRs were certainly not unobtainable, but they were considerably more expensive. Back then, the most comparable device on the market would have been the FUNcube dongle, a nearly $200 USD receiver that was actually designed for receiving data from CubeSats. Anything cheaper than that was likely to be a kit, and often operated within a narrower range of frequencies.

Today, we would argue that an RTL-SDR receiver is a must-have tool. For the cost of a cheap set of screwdrivers, you can gain access to a world that not so long ago would have been all but hidden to the amateur hacker. Let’s take a closer look at a few obvious ways that everyone’s favorite low-cost SDR has helped free the RF hacking genie from its bottle in the last few years.