Join us on Wednesday, April 22 at noon Pacific for the Hacking Apollo Hack Chat with “CuriousMarc” Verdiell, Ken Shirriff, Mike Stewart, and Carl Claunch!

When President Kennedy laid down the gauntlet to a generation of scientists and engineers to land a man on the Moon before the close of the 1960s, he likely had little idea what he was putting in motion. The mission was dauntingly complex, the science was untested, and the engineering was largely untried. Almost everything had to be built from scratch, and entire industries were born just from the technologies that had to be invented to make the dream come true.

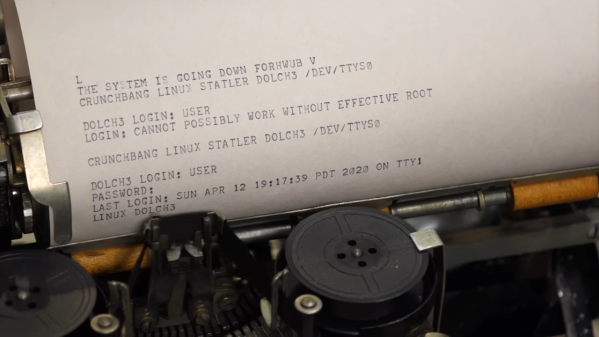

Chief among these new fields was computer science, which was barely in its infancy when the 1960s started. By the end of the decade and the close of the Space Race, computers had gone from room-filling, power-guzzling machines to something compact and capable enough to fly men to the Moon and back. The computers that followed all built on the innovations that came about as a result of Apollo, and investigating the computers of the era and finding out what made them tick is an important part of our technological culture.

That’s where this retrocomputing dream team came into play. Together, they’ve poked and prodded at every bit of hardware from the Space Race era they could find, including a genuine Apollo Guidance Computer (AGC) that was rescued from the trash. What’s more, they actually managed to restore it to working condition with a series of epic hacks and sheer force of will.

Marc, Ken, Mike, and Carl will stop by the Hack Chat to talk about everything that went into getting the AGC working again, along with anything else that pops up. Come ready to have your Apollo-era hardware itches scratched by the people who’ve been inside a lot of it, and who have seen first-hand what it took to make it to the Moon and back.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, April 22 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have got you down, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, April 22 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have got you down, we have a handy time zone converter.

Click that speech bubble to the right, and you’ll be taken directly to the Hack Chat group on Hackaday.io. You don’t have to wait until Wednesday; join whenever you want and you can see what the community is talking about.