There comes a time in every electronic designer’s life when, whether they know it or not, they need an analog filter in their design. If you’re coming from a digital background, where everything is nice and numeric, the harsh reality of continuous voltages can be a bit of a shock. But if you’re taking input from, or sending output to the big analog world out there, it pays to at least think about the frequency-domain properties of the signal, and maybe even do something about them.

Designing an analog filter to fit your needs can be a bit of a daunting task: there are many factors that you’re going to need to consider, and they all interact. It’s easy to get lost. We’re going to simplify this as much as possible by instead focusing on a few common applications and building up the simplest possible filters that work well for them.

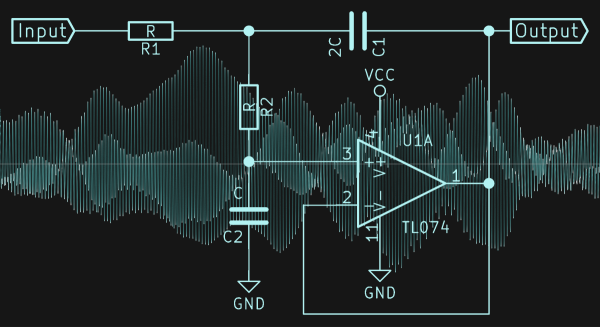

Today, we’re going to consider the lowpass filter, and specifically a Sallen-Key filter with Butterworth characteristics and a second-order rolloff. Sound like word salad? We’ll fix that up right away, because this is probably the single most important filter to have in your analog toolbox for two very common use cases: pulse-width modulated (PWM) output and analog-to-digital conversion (ADC) input.