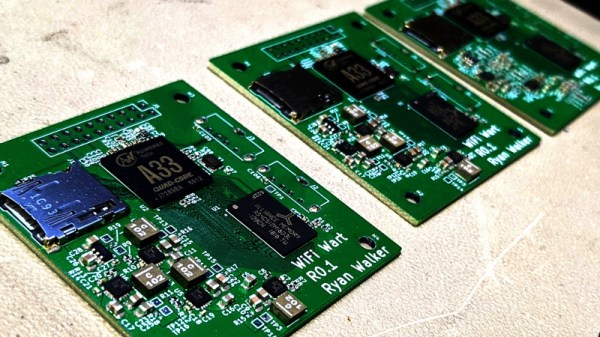

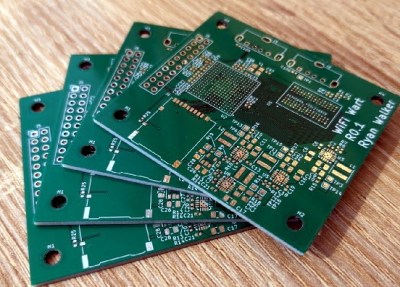

When we last checked in on the WiFiWart, an ambitious project to scratch-build a Linux powered penetration testing drop box small enough to be disguised as a standard phone charger, it was still in the early planning phases. In fact, the whole thing was little more than an idea. But we had a hunch that [Walker] was tenacious enough see the project through to reality, and now less than two months later, we’re happy to report that not only have the first prototype PCBs been assembled, but a community of like minded individuals is being built up around this exciting open source project.

Now before you get too excited, we should probably say that the prototypes didn’t actually work. Even worse, the precious Magic Smoke was released from the board’s Allwinner A33 ARM SoC when a pin only rated for 2.75 V was inadvertently fed 3.3 V. The culprit? Somehow [Walker] says he mistakenly ordered a 3.3 V regulator even though he had the appropriate 2.5 V model down in the Bill of Materials. A bummer to be sure, but that’s what prototypes are for.

Now before you get too excited, we should probably say that the prototypes didn’t actually work. Even worse, the precious Magic Smoke was released from the board’s Allwinner A33 ARM SoC when a pin only rated for 2.75 V was inadvertently fed 3.3 V. The culprit? Somehow [Walker] says he mistakenly ordered a 3.3 V regulator even though he had the appropriate 2.5 V model down in the Bill of Materials. A bummer to be sure, but that’s what prototypes are for.

Even though [Walker] wasn’t able to fire the board up, the fact that they even got produced shows just how much progress has been made in a relatively short amount of time. A lot of thought went into how the 1 GB DDR3 RAM would get connected to the A33, which includes a brief overview of how you do automatic trace length matching in KiCad. He’s also locked in component selections, such as the RTL8188CUS WiFi module, that were still being contemplated as of our last update.

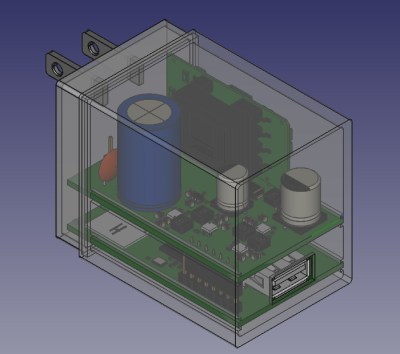

Towards the end of the post, he even discusses the ultimate layout of the board, as the one he’s currently working on is just a functional prototype and would never actually fit inside of a phone charger. It sounds like the plan is to make use of the vertical real estate within the plastic enclosure of the charger, rather than trying to cram everything into a two dimensional design.

Want to get in on the fun, or just stay updated as [Walker] embarks on this epic journey? Perhaps you’d be interested in joining the recently formed Open Source Security Hardware Discord server he’s spun up. Whether you’ve got input on the design, or just want to hang out and watch the WiFiWart get developed, we’re sure he’d be happy to have you stop by.

The first post about this project got quite a response from Hackaday readers, and for good reason. While many in the hacking and making scene only have a passing interest in the security side of things, we all love our little little Linux boards. Especially ones that are being developed in the open.