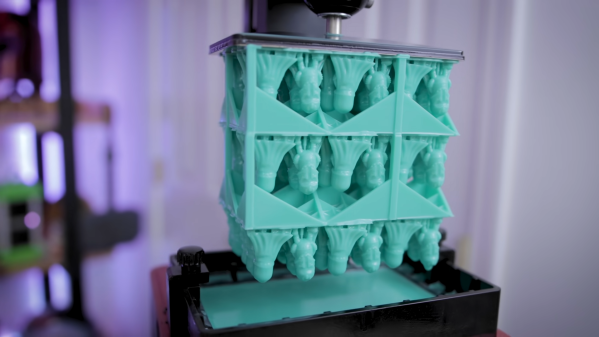

A cycloidal gear drive is one of the most mesmerizing reduction gears to watch when it is running, but it’s not all just eye-candy. Cycloidals give decent gearing, are relatively compact and back-drivable, and have low backlash and high efficiency. You probably want one in the shoulder of your robot arm, for instance.

But designing and building one isn’t exactly straightforward. Thanks, then, to [How To Mechatronics] for the lovely explanation of how it works in detail, and a nice walkthrough of designing and building a cycloidal gear reducer out of 3D printed parts and a ton of bearings. If you just want to watch it go, check out the video embedded below.

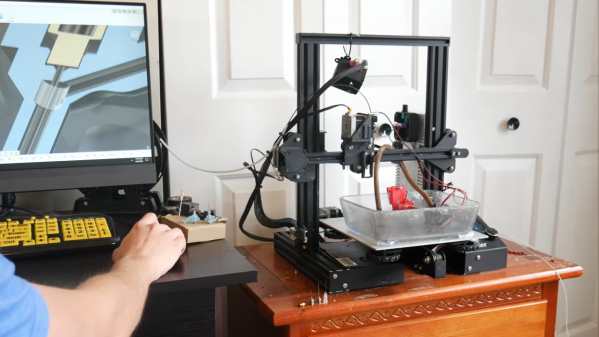

The video is partly an ad for SolidWorks, and spends a lot of time on the mechanics of designing the parts for 3D printing using that software. Still, if you’re using any other graphical CAD tool, you should be able to translate what you learned.

It’s amazing that 3D printing has made sophisticated gearbox designs like this possible to fabricate at home. This stuff used to be confined to the high-end machine shops of fancy robotics firms, and now you can make one yourself this weekend. Not exotic or unreliable enough for you? Well, then, buy yourself some flexible filament and step on up to the strain wave, aka “harmonic drive”, gearbox.

Thanks to serial tipster [Keith] for the tip!