The Game Boy DMG-01 is about as iconic as a piece of consumer electronics can get, but let’s be honest, it hasn’t exactly aged well. While there’s certainly a number of games for the system that are still as entertaining in 2021 as they were in the 80s and 90s, the hardware itself is another story entirely. Having to squint at the unlit display, with its somewhat nauseating green tint, certainly takes away from the experience of hunting down Pokémon.

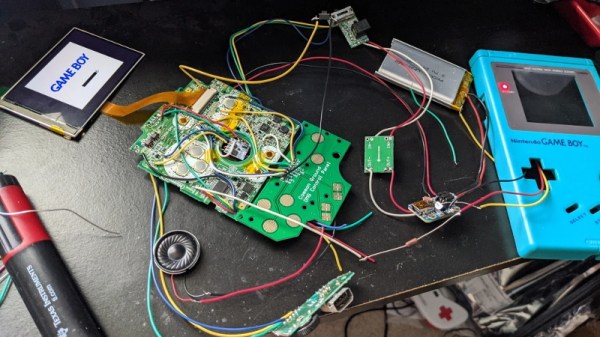

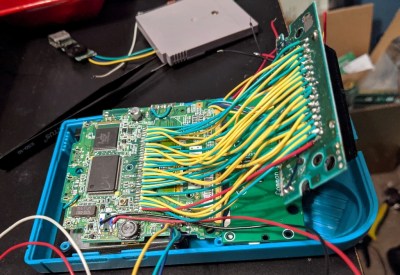

Which is precisely why [The Poor Student Hobbyist] decided to take an original Game Boy and replace its internals with more modern hardware in the form of a Game Boy Advance (GBA) SP motherboard and aftermarket IPS LCD panel. The backwards compatibility mode of the GBA allows him to play those classic Game Boy and Game Boy Color games from their original cartridges, while the IPS display brings them to life in a way never before possible.

Now on the surface, this might seem like a relatively simple project. After all, the GBA SP was much smaller than its predecessors, so there should be plenty of room inside the relatively cavernous DMG-01 case for the transplanted hardware. But [The Poor Student Hobbyist] made things quite a bit harder on himself by deciding early on that there would be no external signs that the Game Boy had been modified; beyond the wildly improved screen, anyway.

That meant deleting the GBA’s shoulder buttons, though since the goal was always to play older games that predated their addition to the system, that wasn’t really a problem. The GBA’s larger and wider screen is still intact, albeit hidden behind the Game Boy’s original bezel. It turns out the image isn’t exactly centered on the physical display, so [The Poor Student Hobbyist] came up with a 3D printed adapter to mount it with a slight offset. The adapter also allows the small tactile switch that controls the screen brightness to be mounted where the “Contrast” wheel used to go.

An incredible amount of thought and effort went into making the final result look as close to stock as possible, and luckily for us, [The Poor Student Hobbyist] did a phenomenal job of documenting it for others who might want to make similar modifications. Even if you’re not in the market for a rejuvenated Game Boy, it’s worth browsing through the build log to marvel at the passion that went into this project.

Some would argue [The Poor Student Hobbyist] should have just put a Raspberry Pi into a Game Boy case and be done with it, but where’s the fun in that? Sure it might have been a somewhat better Bitcoin miner, but there’s something to be said for playing classic games on real hardware.