We recently looked at the origins of the integrated circuit (IC) and the calculator, which was the IC’s first killer app, but a surprise twist is that the calculator played a big part in the invention of the next world-changing marvel, the microprocessor.

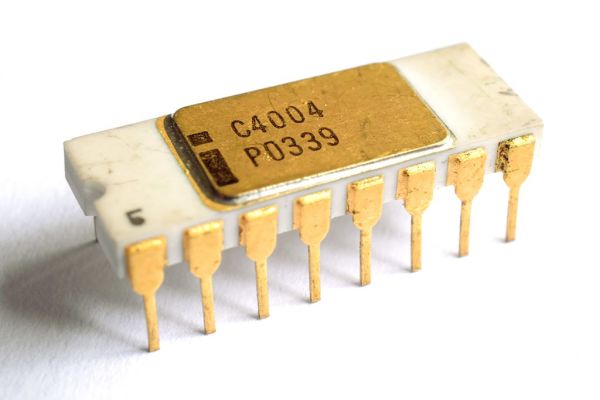

There is some dispute as to which company invented the microprocessor, and we’ll talk about that further down. But who invented the first commercially available microprocessor? That honor goes to Intel for the 4004.

Path To The 4004

We pick up the tale with Robert Noyce, who had co-invented the IC while at Fairchild Semiconductor. In July 1968 he left Fairchild to co-found Intel for the purpose of manufacturing semiconductor memory chips.

While Intel was still a new startup living off of their initial $3 million in financing, and before they had a semiconductor memory product, as many start-ups do to survive they took on custom work. In April 1969, Japanese company Busicom hired them to do LSI (Large-Scale Integration) work for a family of calculators.

Busicom’s design, consisting of twelve interlinked chips, was considered a complicated one. For example, it included shift-register memory, a serial type of memory which complicates the control logic. It also used Binary Coded Decimal (BCD) arithmetic. Marcian Edward Hoff Jr — known as “Ted”, head of the Intel’s Application Research Department, felt that the design was even more complicated than a general purpose computer like the PDP-8, which had a fairly simple architecture. He felt they may not be able to meet the cost targets and so Noyce gave Hoff the go-ahead to look for ways to simplify it.

Continue reading “Inventing The Microprocessor: The Intel 4004”