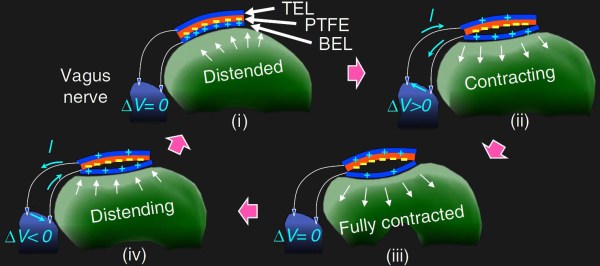

Controlled electrical stimulation of nerves can do amazing things. It has been shown to encourage healing and growth in damaged cells of the peripheral nervous system which means regaining motor control and sensation in a shorter period with better results. This type of treatment is referred to as an electroceutical, and the etymology is easy to parse. The newest kid on the block just finished testing on rat subjects, applying electricity for one, three, or six days per week in one-hour intervals. The results showed that more treatment led to faster healing. The kicker is that the method of applying electricity was done through unbroken skin on an implant that dissolves harmlessly.

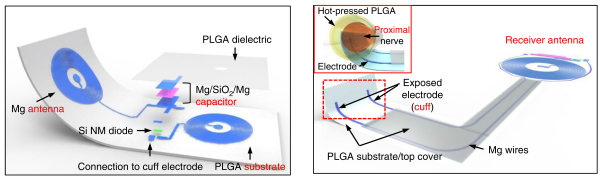

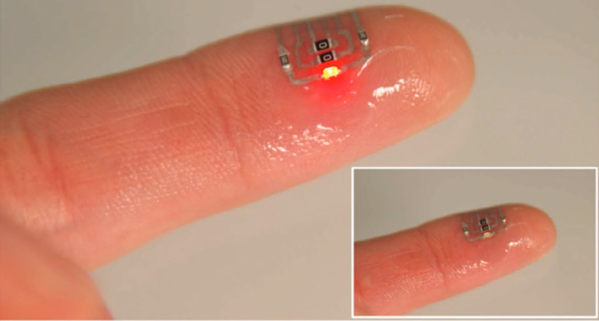

The implant in question is, at its most basic, an RFID tag with leads that touch the injured nerves. This means wireless magnetic coupling takes power from an outside source and delivers it to where it is needed. All the traces on are magnesium. There is a capacitor with silicon dioxide sandwiched between magnesium, and a diode made from a doped silicon nanomembrane. All this is encased in a biodegradable substrate called poly lactic-co-glycolic acid, a rising star for FDA-approved polys. Technologically speaking, these are not outrageous.

These exotic materials are not in the average hacker’s hands yet, but citizen scientists have started tinkering with the less invasive tDCS and which is applying a small electrical current to the brain through surface electrodes or the brain hacking known as the McCollough effect.

Via IEEE Spectrum.