The Internet of Things is a cancer that consumes all reasonable expectations of technology, opens vast security holes we’ve never had to deal with before, and complicates life in the pursuit of quarterly gains from whatever technology startup is hot right now. We are getting some interesting tech out of it, though. The latest in the current round of ‘I can’t believe someone would build that’ is the Internet of Pillows. No, it’s not a product, it’s just an application note, but it does allow us to laugh at the Internet of Things while simultaneously learning about some really cool chips.

The idea behind this ‘smart’ pillow is to serve as a snoring sensor. When the smart pillow detects the user is snoring, a small vibration motor turns on to wake up the user. There’s no connectivity in this smart pillow, so the design is relatively straightforward. You need a microphone or some sort of audio sensor, you should probably have a force-sensitive resistor so you know the pillow is actually being used, and you need a vibration motor. Throw in a battery for good measure. Aside from that, you’re also going to need a microcontroller, and that’s where things get interesting.

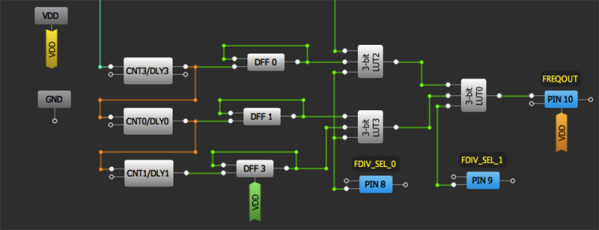

This application note was written as a demonstration of what Dialog’s GreenPAC devices can do. We’ve seen these things before, and the idea behind these devices is something like a ‘modern-day PAL’ or ‘a really, really limited FPGA’. It’s a bit more than that, though, because the GreenPAC devices are mixed-signal, there are some counters and latches in there, and all the programming is done through a graphical IDE. If you need a small, low-power chip that only does one thing, the GreenPAC is right up your alley.

So, how does this device detect snoring? The code pulls data from the sound sensor every 30 ms, with a 5 ms time window. If this sound repeats again within six seconds, it’s assumed the user is snoring. The logic then turns on the vibration motor, greatly annoying whoever is sleeping. All of this is done through a graphical IDE, which I’m sure will draw the ire of some, but there really aren’t that many pins or that many LUTs on GreenPAC devices, so it’s never going to get too out of hand.

The GreenPAC is a very interesting family of parts that we don’t see too much of around here. That’s a shame, because for low-power applications that don’t need a lot of horsepower, the GreenPAC seems like it would be very useful. Slightly more useful than an Internet of Things pillow, at least.