Regular followers of space news will know that when satellites or space probes reach the end of their life, they either are de-orbited in a fiery re-entry, or they stay lifeless in orbit, often in a safe graveyard orbit where they are unlikely to harm other craft. Sometimes these deactivated satellites spring back into life, and there is a dedicated band of enthusiasts who seek out these oddities. Dead satellite finder extraordinaire [Scott Tilley] has turned up a particularly unusual one, a craft that is quite likely to be the oldest still-working geostationary satellite.

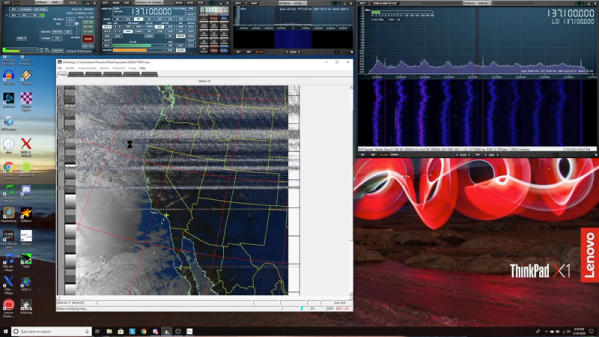

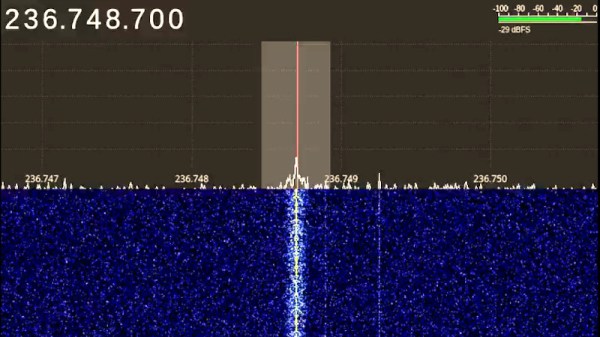

LES-5 is an experimental satellite built by MIT’s Lincoln Labs, launched in 1967, and used to test military UHF communications in a geosynchronous orbit. It had an active life into the early 1970s after which it was placed in a graveyard orbital slot for redundant craft. It’s lain forgotten ever since, until this month when [Scott] found its beacon transmitting on 236.75 MHz. The Twitter thread is an extremely interesting glimpse into the satellite finder’s art, as first he’s not certain at all that it is LES-5 so he waits for its solar eclipse to identify its exact position.

Whether anything on the craft can find another use today is not certain, as he finds no evidence of its transponder. Still, that something is working again 53 years after its launch is a testament to the quality of its construction. Should its transponder be reactivated again it’s not impossible that people might find illicit uses for it, after all that’s not the first time this has happened.

Alternately referred to as the “DARPA Experimental Spaceplane”, the vehicle was envisioned as being roughly the size of a business jet and capable of carrying a payload of up to 2,300 kilograms (5,000 pounds). It would take off vertically under rocket power and then glide back to Earth at the end of the mission to make a conventional runway landing. At $5 million per flight, its operating costs would be comparable with even the most aggressively priced commercial launch providers; but with the added bonus of not having to involve a third party in military and reconnaissance missions which would almost certainly be classified in nature.

Alternately referred to as the “DARPA Experimental Spaceplane”, the vehicle was envisioned as being roughly the size of a business jet and capable of carrying a payload of up to 2,300 kilograms (5,000 pounds). It would take off vertically under rocket power and then glide back to Earth at the end of the mission to make a conventional runway landing. At $5 million per flight, its operating costs would be comparable with even the most aggressively priced commercial launch providers; but with the added bonus of not having to involve a third party in military and reconnaissance missions which would almost certainly be classified in nature.