Anyone who has ever gone to a bowling alley will know the preferred (but ineffective) technique to telepathically control a bowling ball. [Mark Rober] and [James Bruton] decided to change that and hacked a bowling ball that can be steered remotely (and discreetly), simply by leaning your body.

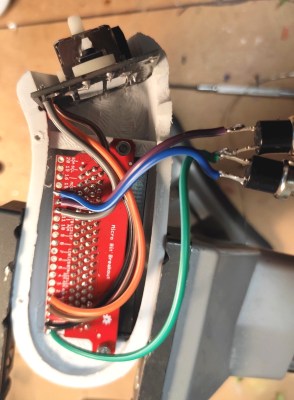

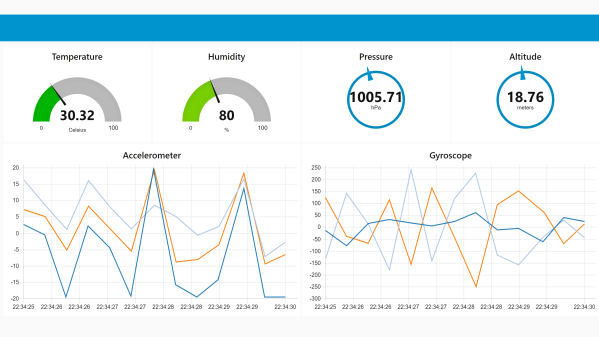

They started with a standard bowling ball, that was  cut in half and hollowed out on a lathe. A beam sits on the centre line of the ball, mounted on a bearing in each half to allow the ball to spin around it. Steering done by shifting the centre of mass, by moving a steel pendulum that hangs below the beam side to side with heavy-duty servo. The servo is controlled with an Arduino, and an IMU to detects the balls orientation. Power is provided by and RC Lipo battery. The wireless controller is a sneaky little device that is taped to [Mark]’s back and covered with clothing, and steers the ball by detecting how far he leans with an IMU module. The brain is an Arduino Mini and an NRF24L01 provides the RF link.

cut in half and hollowed out on a lathe. A beam sits on the centre line of the ball, mounted on a bearing in each half to allow the ball to spin around it. Steering done by shifting the centre of mass, by moving a steel pendulum that hangs below the beam side to side with heavy-duty servo. The servo is controlled with an Arduino, and an IMU to detects the balls orientation. Power is provided by and RC Lipo battery. The wireless controller is a sneaky little device that is taped to [Mark]’s back and covered with clothing, and steers the ball by detecting how far he leans with an IMU module. The brain is an Arduino Mini and an NRF24L01 provides the RF link.

While it’s not an easy build, it’s a fairly simple system electronically, with off the shelf electronics modules and perfboard. The genius is in the implementation and its entertainment value. The look on the kids faces when [Mark] “telepathically” controls the ball, after showing off the fact that he has zero natural ability, is absolutely priceless. [Mark Rober], a former NASA engineer, has made a name for himself with viral Youtube videos on cool projects like a glitter booby trap for package thieves and a liquid sand hot tub. [James Bruton], a former toy designer is known for his robotics prowess that he has put on display with OpenDog and functional Star Wars robots.

For us this hack is a perfect example of one that entertains and inspires, a powerful combination for young and old alike. Check out the awesome video after the break. Continue reading “Cheating At Bowling, The Hacker Way”