The real world is analog, and the op-amp is the indispensable building block of many analog circuits. We wanted to give you analog fanatics out there a chance to shine and to encourage our digital brothers and sisters to dip their toes in the murky waters where ones and zeroes define the ends of a spectrum rather than representing the only choice. Hence, we presented the Op Amp Challenge. And you did not disappoint!

We received 83 entries, and it was extraordinarily hard to pick the winners. But since we had three $150 DigiKey shopping sprees to give away, our six judges buckled down and picked their favorites. Whether or not you’ve got the Golden Rules of the ideal op-amp tattooed on your arm, you’ll enjoy looking through all of the projects here. But without further ado…

The Winners

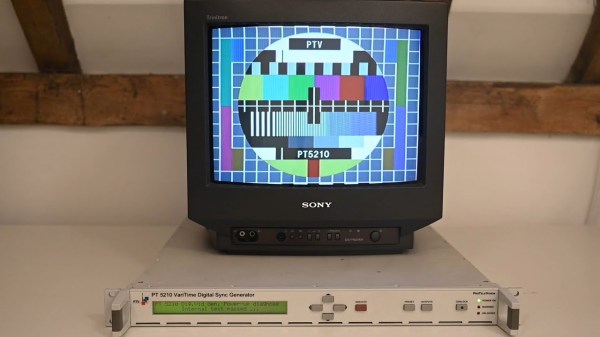

[Craig]’s Op Art is an X-Y voltage generator to plug into an oscilloscope and make classic Lissajous and other spirograph-like images, and it’s all done in analog. Maybe it was his incredible documentation, the nice use of a classic three-op-amp tunable oscillator, or the pun hidden in the title. Whatever the case, it wowed our judges and picked up a deserved place in the top three.

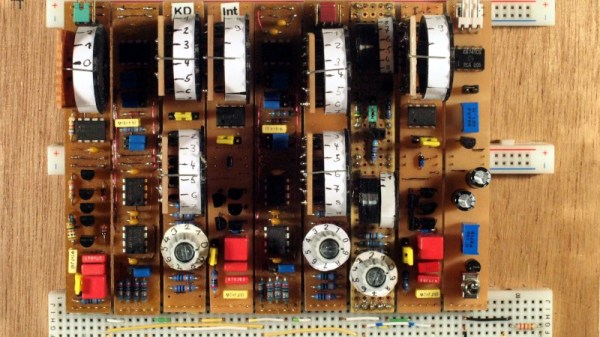

Hearkening back to the pre-digital dinosaur days, [Rainer Glaschick]’s Flexible Analog Computer is a modular analog computer prototyping system on a breadboard backplane. Since you have to re-wire up an analog computer for your particular, it’s great that [Rainer] gave us a bunch of examples on his website as well, including a lunar lander and classic Lorenz attractor demos.

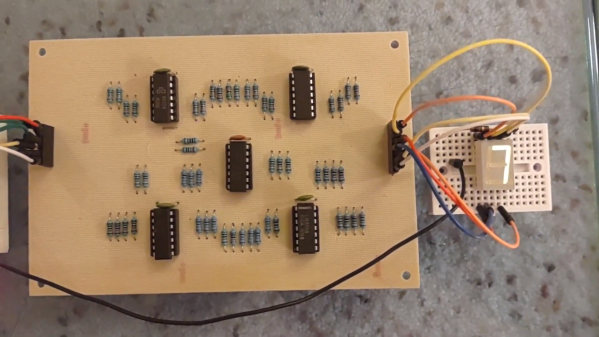

And there was no way that [Chris]’s interactive analog LED wave array wouldn’t place in the top three. It’s a huge 2D analog simulation that runs entirely on op-amps, sensing when your hand moves across any part of its surface and radiating waves out from there. You have to admire the massive scale here, and you simply must check out the video of it in action. Glorious!

Continue reading “Congratulations To Our Op-Amp Challenge Winners!”