While certain dystopian visions of the future have humans power the grid for AIs, Microsoft and Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL) set a machine learning system on the path of better solid state batteries instead.

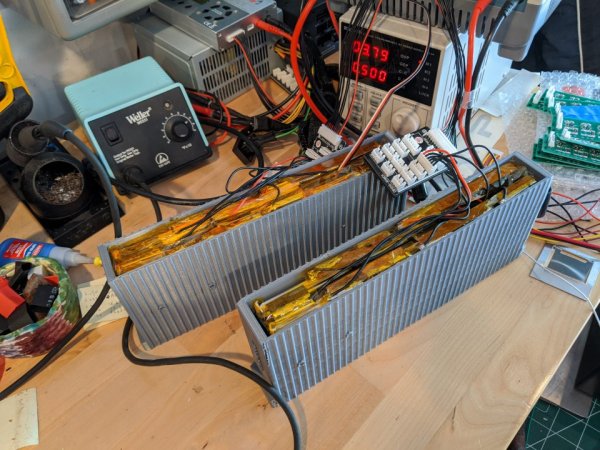

Solid state batteries are the current darlings of battery research, promising a step-change in packaging size and safety among other advantages. While they have been working in the lab for some time now, we’re still yet to see any large-scale commercialization that could shake up the consumer electronics and electric vehicle spaces.

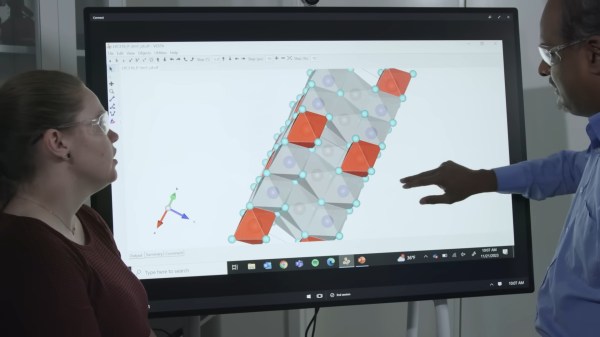

With a starting set of 32 million potential inorganic materials, the machine learning algorithm was able to select the 150 most promising candidates for further development in the lab. This smaller subset was then fed through a high-performance computing (HPC) algorithm to winnow the list down to 23. Eliminating previously explored compounds, the scientists were able to develop a promising Li/Na-ion solid state battery electrolyte that could reduce the needed Li in a battery by up to 70%.

For those of us who remember when energy materials research often consisted of digging through dusty old journal papers to find inorganic compounds of interest, this is a particularly exciting advancement. A couple more places technology can help in the sciences are robots doing the work in the lab or on the surgery table.