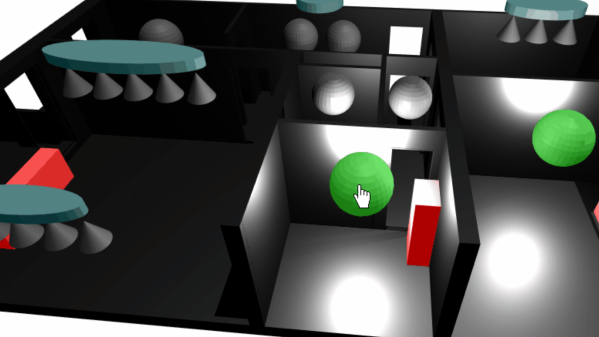

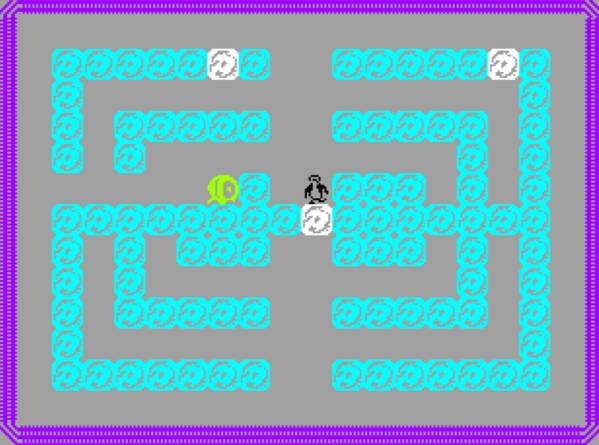

With an ever-growing range of smart-home products available, all with their own hubs, protocols, and APIs, we see a lot of DIY projects (and commercial offerings too) which aim to provide a “single universal interface” to different devices and services. Usually, these projects allow you to control your home using a list of devices, or sometimes a 2D floor plan. [Wassim]’s project aims to take the first steps in providing a 3D interface, by creating an interactive smart-home controller in the browser.

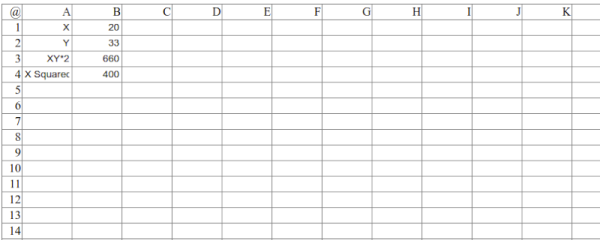

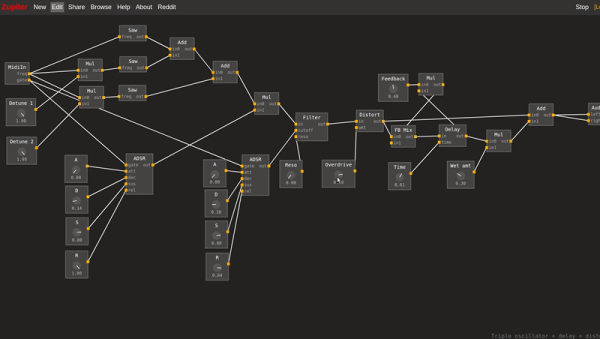

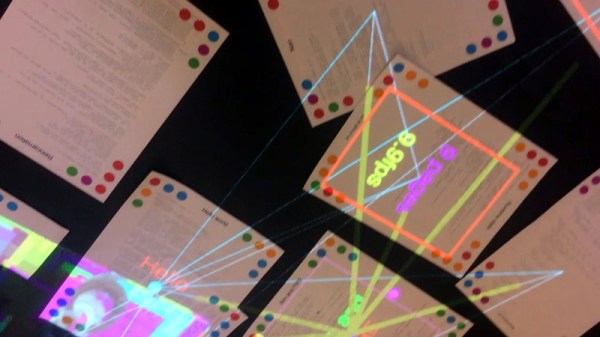

Note: this isn’t just a rendered image of a 3D scene which is static; this is an interactive 3D model which can be orbited and inspected, showing information on lights, heaters, and windows. The project is well documented, and the code can be found on GitHub. The tech works by taking 3D models and animations made in Blender, exporting them using the .glTF format, then visualising them in the browser using three.js. This can then talk to Hue bulbs, power meters, or whatever other devices are required. The technical notes on this project may well be useful for others wanting to use the Blender to three.js/browser workflow, and include a number of interesting demos of isolated small key concepts for the project.

We notice that all the meshes created in Blender are very low-poly; is it possible to easily add subdivision surface modifiers or is it the vertex count deliberately kept low for performance reasons?

This isn’t our first unique home automation interface, we’ve previously written about shAIdes, a pair of AI-enabled glasses that allow you to control your devices just by looking at them. And if you want to roll your own home automation setup, we have plenty of resources. The Hack My House series contains valuable information on using Raspberry Pis in this context, we’ve got information on picking the right sensors, and even enlisting old routers for the cause.