A robot that performs surgery is a serious thing. One bug in the control system could end with disaster. Unless of course, you’re [Michael Reeves], in which case disaster is all part of the fun. (Video, embedded below.)

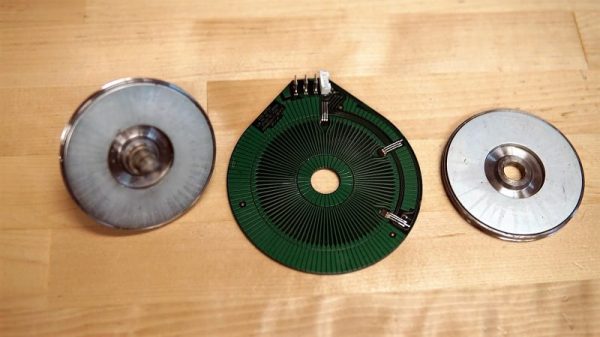

Taking inspiration from The da Vinci Surgical System, [Michael] set out to build a system that was faster, while still maintaining precision. He created a belt drive gantry system, not unlike many 3D printers, laser cutters, or woodworking CNC machines. Machines like this often use stepper motors. [Michael] decided to go with [Oskar Weigl’s] ODrive and brushless motors instead. The ODrive is on open source controller which turns off the shelf brushless motors — such as those found in R/C planes or hoverboards, into precision industrial servos. Sound familiar? ODrive was an entrant in the 2016 Hackaday Prize. [Michael] was even able to do away the ubiquitous limit switch by monitoring current draw with the ODrive.

It all adds up to a serious build. But this is [Michael “laser eye” Reeves] after all. The video is meant to be entertaining, with a hidden payload of education and inspiration. The fun starts when he arms the robot with a giant kitchen knife and performs “surgery” on a pineapple. If you want to know what happens when mannequins and fake blood enter the picture, then watch the video after the break.