Some woodworking operations require stock to be fed at a smooth, steady rate, for which purpose a power feeder is usually employed. They’re expensive bits of gear, though, and their cost can usually be borne only by high-output production shops. But when you need one, you need one, and hacking a power feeder from a drill and a skate wheel is a viable option.

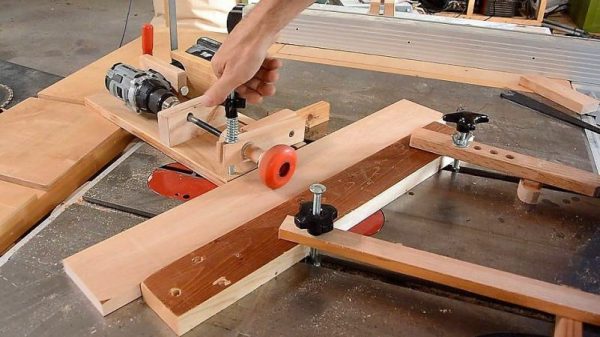

It should come as no surprise that this woodshop hack comes to us from [Matthias Wandel], who never seems to let a woodworking challenge pass him by. His first two versions of expedient power feeders were tasked with making a lot of baseboard moldings in his new house. Version three, presented in the video below, allows him to feed stock diagonally across his table saw, resulting in custom cove moldings. The completed power feeder may look simple — it’s just a brushless drill in a wooden jig driving a skate wheel — but the iterative design process [Matthias] walks us through is pretty fascinating. We also appreciate the hacks within hacks that always find their way into his videos. No lathe? No problem! Improvise with a drill and a bandsaw.

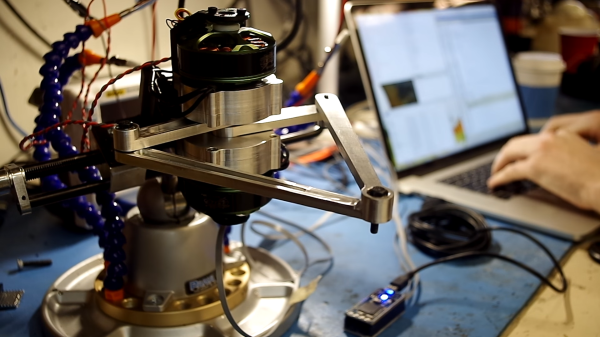

Surprised that [Matthias] didn’t use some of his famous wooden gears in this build? We’re not. A brushless motor is perfect for this application, with constant torque at low speeds. Want to learn more about BLDC motors? Get the basics with a giant demo brushless motor.

Continue reading “Smooth And Steady Cuts With An Improvised Power Feeder”