It’s the [Bruce Land]-iest season of all, when the Cornell professor submits the projects his microcontroller class students have been working on all semester. Imagination does not seem to be in short supply with these students, and we always look forward to these tips this time of year.

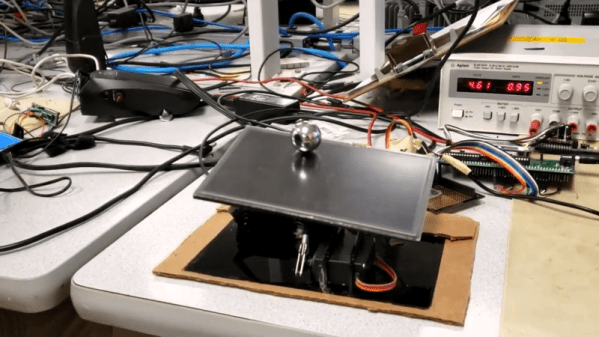

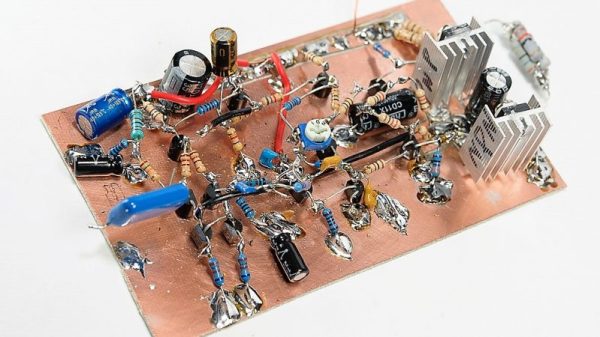

[Greg] and [Sam]’s touch-screen two-dimensional ball balancer is a good example of what [Land]’s students turn out. The resistive touch screen is supported by a 3D-printed gimballed platform and tilted in two axes by hobby servos. [Greg] and [Sam] chose to read the voltage outputs from the touch screen directly using the ADC on a PIC32, toggling between the two axes at 2 kHz. Two PID control loops were implemented to keep the ball as centered as possible on the platform, and the video below shows that there’s still some loop tuning to do. But given the positional inaccuracies of hobby servos and the compliance in the gimbal, we’re impressed that they were able to keep the system under control at all.

Of course we’ve seen ball-balancers before, but most of them have closed the loop using either cameras or microphones. Seeing direct sensing on the platform like this is a nice change of pace. Continue reading “2D-Platform Seeks Balance With A Touch Screen”