If you have a Hello Sense sleep tracking device lying around somewhere in your drawer of discards, it can be brought back to life in a new avatar. Just follow [Alexander Gee]’s instructions to resurrect the Hello Sense as an IoT air quality data-logger.

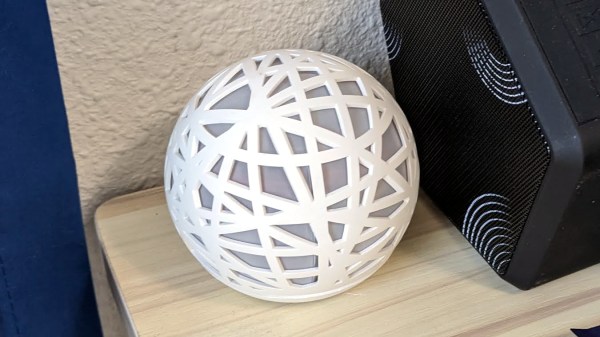

In 2014, startup “Hello” introduced the Sense, an IoT sleep tracking device with a host of embedded sensors, all wrapped up in a slick, injection molded spherical enclosure. The device was quite nice, and by 2015, they had managed to raise $21M in funding. But their business model didn’t seem sustainable, and in 2017, Hello shut shop. Leaving all the Sense devices orphaned, sitting dormant in beautifully designed enclosures with no home to dial back to.

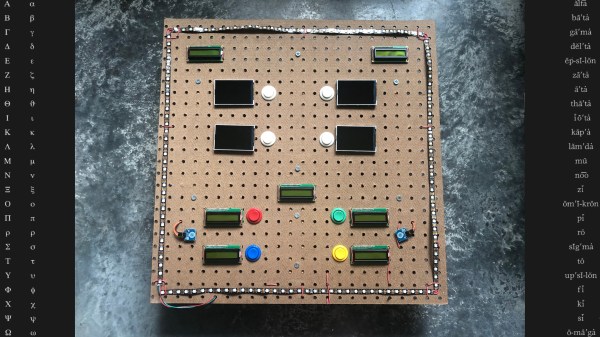

The original Sense included six sensors: illumination, humidity, temperature, sound, dust / particulate matter on the main device, and motion sensing via a separate Bluetooth dongle called the Pill. [Alexander] was interested in air quality measurements, so only needed to get data from the humidity/temperature and dust sensors. Thankfully for [Alexander], a detailed Hello Sense Teardown by [Lindsay Williams] was useful in getting started.

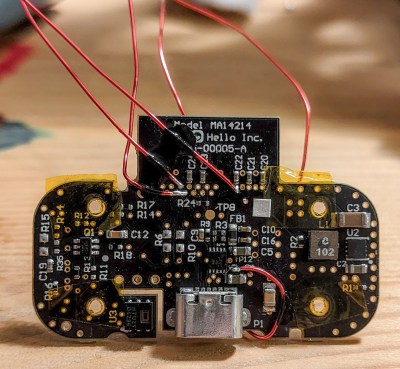

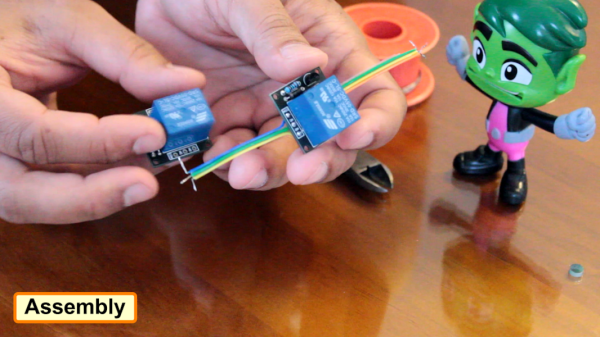

The hardware consisted of four separate PCB’s — power conditioning, LED ring, processor, and sensor board. This ensured that everything could be fit inside the orb shaped enclosure. Getting rid of the LED ring and processor board made space for a new NodeMCU ESP8266 brain which could be hooked up to the sensors. Connecting the NodeMCU to the I2C interface of the humidity/temperature sensor required some bodge wire artistry. Interfacing the PM sensor was a bit more easier since it already had a dedicated cable connected to the original processor board which could be reconnected to the new processor board. The NodeMCU board runs a simple Arduino sketch, available on his Git repo, to gather data and push it online.

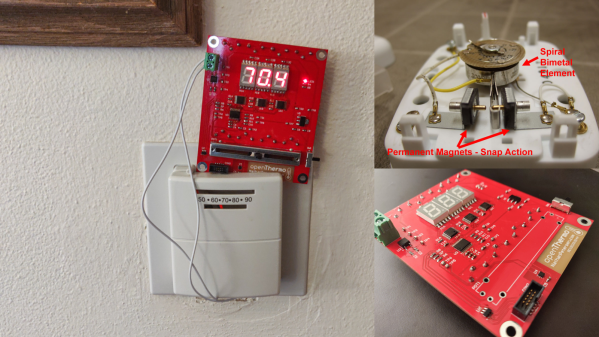

For the online data display dashboard, [Alexander] found a nice solution by [Nilhcem] for home monitoring using MQTT, InfluxDB, and Grafana. It could be deployed via a docker compose file and have it up and running quickly. Unfortunately, such projects don’t usually succeed without causing some heartburn, so [Alexander] has got you covered with a bunch of troubleshooting tips and suggestions should you get entangled.

If you have an old Sense device lying around, then this would be a good way to put it some use. But If you’d rather build an air-quality monitor from scratch, then try “Building a Full-Fat Air-Quality Monitor” or “An Air-quality Monitor That Leverages the Cloud“.