BIQU has released a new line of low-temperature build plates that look to be the next step in 3D printing’s iteration—or so YouTuber Printing Perspective thinks after reviewing one. The Cryogrip Pro is designed for the Bambu X1, P1, and A1 series of printers but could easily be adapted for other magnetic-bed machines.

The idea of the new material is to reduce the need for high bed temperatures, keeping enclosure temperatures low. As some enclosed printer owners may know, trying to print PLA and even PETG with the door closed can be troublesome due to how slowly these materials cool. Too high an ambient temperature can wreak havoc with this cooling process, even leading to nozzle-clogging.

The new build plate purports to enable low, even ambient bed temperatures, still with maximum adhesion. Two versions are available, with the ‘frostbite’ version intended for only PLA and PETG but having the best adhesion properties. A more general-purpose version, the ‘glacier’ sacrifices a little bed adhesion but gains the ability to handle a much wider range of materials.

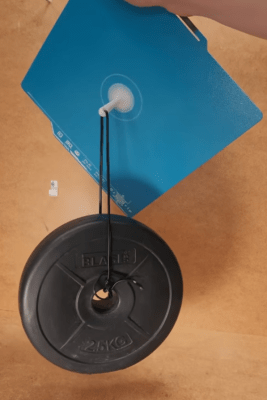

An initial test with a decent-sized print showed that the bed adhesion was excellent, but after removing the print, it still looked warped. The theory was that it was due to how consistently the magnetic build plate was attached to the printer bed plate, which was now the limiting factor. Switching to a different printer seemed to ‘fix’ that issue, but that was really only needed to continue the build plate review.

They demonstrated a common issue with high-grip build plates: what happens when you try to remove the print. Obviously, magnetic build plates are designed to be removed and flexed to pop off the print, and this one is no different. The extreme adhesion, even at ambient temperature, does mean it’s even more essential to flex that plate, and thin prints will be troublesome. We guess that if these plates allow the door to be kept closed, then there are quite a few advantages, namely lower operating noise and improved filtration to keep those nasty nanoparticles in check. And low bed temperatures mean lower energy consumption, which is got to be a good thing. Don’t underestimate how much power that beefy bed heater needs!

Ever wondered what mini QR-code-like tags are on the high-end build plates? We’ve got the answer. And now that you’ve got a pile of different build plates, how do you store them and keep them clean? With this neat gadget!

Continue reading “Putting The New CryoGrip Build Plate To The Test”