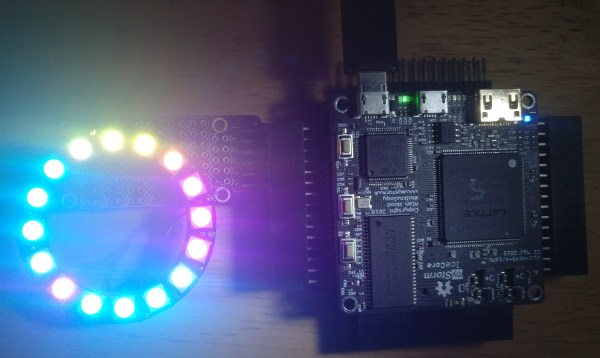

We always can use more tools for FPGA debugging, and the Manta project by [Fischer Moseley] delivers without a shadow of a doubt. Manta lets you add a debug and data transfer channel between your computer and your FPGA, that you can easily access with helpfully included Python libraries.

With just a short configuration file as input, it gives you cores you add into your FPGA design, tapping the signals of interest as an FPGA-embedded logic analyzer, interacting with registers, and even letting you quickly transfer tons of data if you so desire.

Manta is easy to install, is developer-friendly, has been designed in Amaranth, and is fully open source as you would expect. At the moment, Manta supports both UART and Ethernet interfaces for data transfer. As for embedding the Manta cores into your project, they can be exported to both Amaranth and Verilog. You should check out the documentation website — it contains everything you might want to know to get started quick.

The Manta project has started out as our hacker’s MIT thesis, and we’re happy that we can cover it for you all. FPGA-embedded logic analyzers are a fascinating and much-needed tool, and we’ve had our own [Al Williams] tell you about his on-FPGA logic analysis journey!