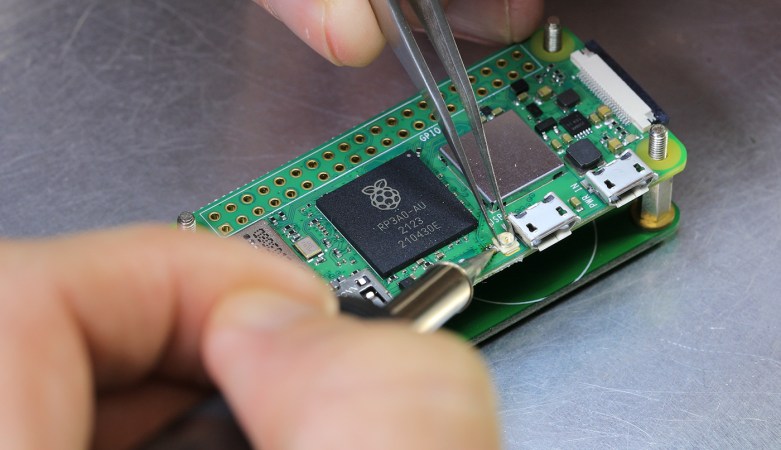

We’ve only started to tap into the potential of the brand new Pi Zero 2. Having finally received his board, [Brian Dorey] shows us how to boost your Pi’s WiFi, the hacker way. Inline with the onboard WiFi antenna can be found a u.FL footprint, and you just know that someone had to add an external antenna. This is where [Brian] comes in, with a photo-rich writeup and video tutorial, embedded below, that will have you modify your own Zero in no time. His measurements show seeing fourteen networks available in a spot where he’d only see four before, and the RSSI levels reported have improved by 5 dB -10 dB, big when it comes to getting a further or more stable connection.

With old laptops being a decent source of WiFi antennas, you only need to procure a u.FL connector and practice soldering a bit before you take this on! The hardest part of such a project tends to be not accidentally putting any solder on the u.FL connector’s metal can – and [Brian] mostly succeeds in that! He shows how to disconnect the external antenna to avoid signal reflections and the like, and, of course, you will be expected to never power your Pi Zero on without an attached antenna afterwards, lest you have your transmitter become fatally confused by the mismatch of hardware-defined impedance expectations. A Pi Zero isn’t the only place where you’ll encounter footprints for connectors you can add, and arguably, that’s your duty as a hacker – modifying the things you work with in a way that adds functionality. Don’t forget to share how you did it!

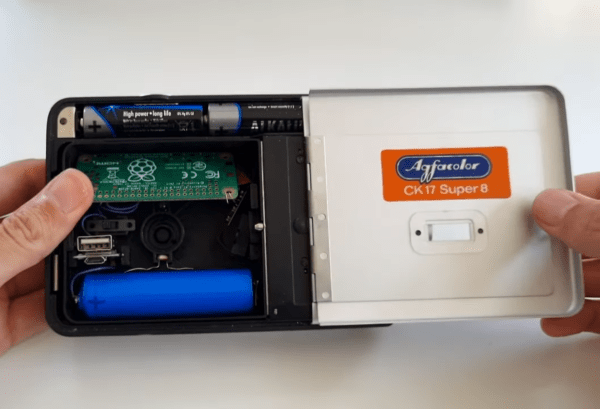

This trick should be pretty helpful if you’re ever to put your new Pi Zero in a full-metal enclosure. Curious about the Raspberry Pi antenna’s inner workings? We’ve covered them before! If you’d like to see some previous Raspberry Pi mods, here’s one for the Pi 3, and here’s one for the original Zero W – from [Brian], too!

Continue reading “New Pi Zero Gains Unapproved Antennas Yet Again”

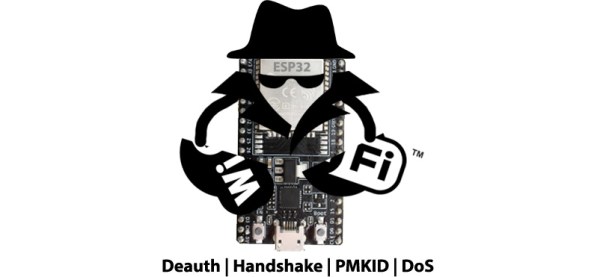

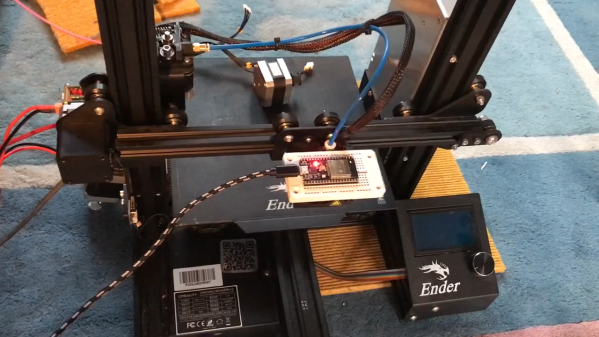

Granted, based as it is on the gantry of an old 3D printer, [Neumi]’s WiFi scanner has a somewhat limited work envelope. A NodeMCU ESP32 module rides where the printer’s extruder normally resides, and scans through a series of points one centimeter apart. A received signal strength indicator (RSSI) reading is taken from the NodeMCU’s WiFi at each point, and the position and RSSI data for each point are saved to a CSV file. A couple of Python programs then digest the raw data to produce both 2D and 3D scans. The 3D scans are the most revealing — you can actually see a 12.5-cm spacing of signal strength, which corresponds to the wavelength of 2.4-GHz WiFi. The video below shows the data capture process and some of the visualizations.

Granted, based as it is on the gantry of an old 3D printer, [Neumi]’s WiFi scanner has a somewhat limited work envelope. A NodeMCU ESP32 module rides where the printer’s extruder normally resides, and scans through a series of points one centimeter apart. A received signal strength indicator (RSSI) reading is taken from the NodeMCU’s WiFi at each point, and the position and RSSI data for each point are saved to a CSV file. A couple of Python programs then digest the raw data to produce both 2D and 3D scans. The 3D scans are the most revealing — you can actually see a 12.5-cm spacing of signal strength, which corresponds to the wavelength of 2.4-GHz WiFi. The video below shows the data capture process and some of the visualizations.