After two massive hurricanes impacted Puerto Rico three months ago, the island was left with extensive damage to its electrical infrastructure. Part of the problem was that the infrastructure was woefully inadequate to withstand a hurricane impact at all. It is possible to harden buildings and infrastructure against extreme weather, and a new plan to restore Puerto Rico’s power grid will address many of these changes that, frankly, should have been made long ago.

Among the upgrades to the power distribution system are improvements to SCADA systems. SCADA allows for remote monitoring and control of substations, switchgear, and other equipment which minimizes the need for crews to investigate problems and improves reliability. SCADA can also be used for automation on a large scale, in addition to the installation of other autonomous equipment meant to isolate faults and restore power quickly. The grid will get physical upgrades as well, including equipment like poles, wire, and substations that are designed and installed to a more rigorous standard in order to make them more wind- and flood-tolerant. Additional infrastructure will be placed underground as well, and a more aggressive tree trimming program will be put in place.

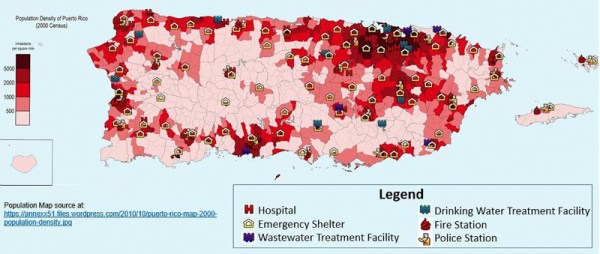

The plan also calls for some 21st-century improvements as well, including the implementation of “micro grids”. These micro grids reduce the power system’s reliance on centralized power plants by placing small generation facilities (generators, rooftop solar, etc) in critical areas, like at hospitals. Micro grids can also be used in remote areas to improve reliability where it is often impractical or uneconomical to service.

While hurricanes are inevitable in certain parts of the world, the damage that they cause is often exacerbated by poor design and bad planning. Especially in the mysterious world of power generation and distribution, a robust infrastructure is extremely important for the health, safety, and well-being of the people who rely on it. Hopefully these steps will improve Puerto Rico’s situation, especially since this won’t be the last time a major storm impacts the island.