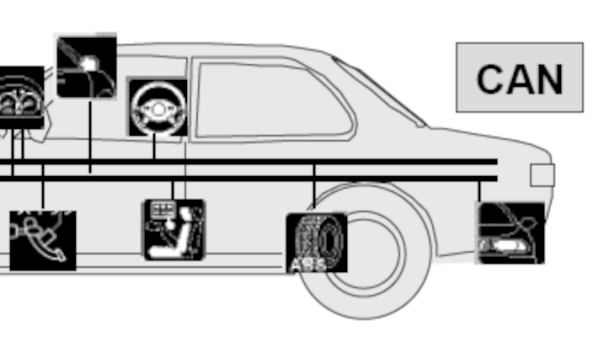

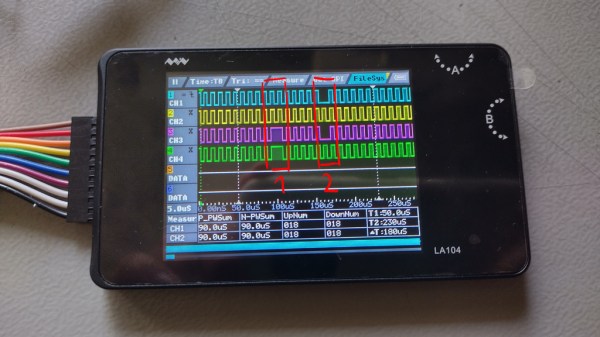

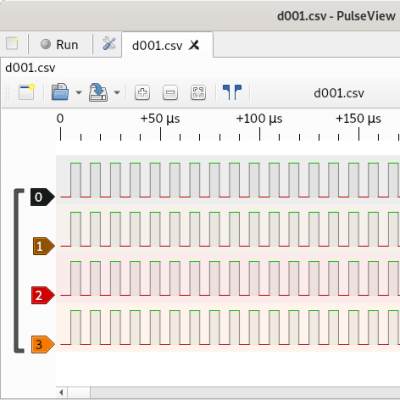

[Kevin O’Connor] writes to us about his project, can2040 – adding CAN support to the RP2040. The RP2040 doesn’t have a CAN peripheral, but [Kevin] wrote code for the RP2040’s PIO engine that can receive and send CAN packets. Now we can all benefit from his work by using this openly available CAN driver. This library is written in C, so it’s a good fit for the lower-level hackers among us, and in all likelihood, it wouldn’t be hard to make a MicroPython wrapper around it.

The CAN bus needs a peripheral for the messages to be handled properly, and people have been using external chips for this purpose until now. These chips, [Kevin] tells us, have lately been unavailable due to the chip shortage, making this project more valuable. The documentation is extensive and accessible, and [Kevin] details how to best use this driver. With such a tool in hand, you can now turn your Pico into a CAN tinkering toolkit, or wire up some CAN devices for use in your own projects!

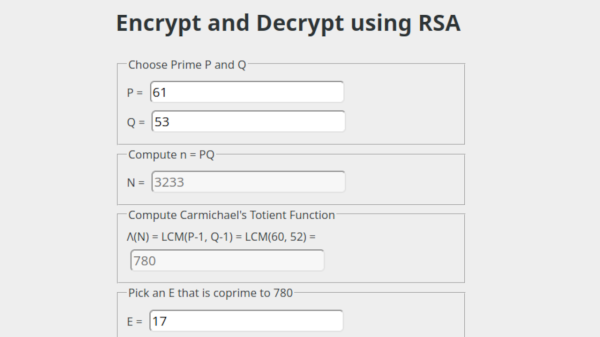

[Kevin] says this code is already being used in Klipper, a framework powering 3D printers and other machines like them. As for your own purposes, you can absolutely use such a CAN tool to hack on your car – here’s a treasure trove of car hacking documentation, by the way! Thanks to the PIO engine, there seems to be no end to the RP2040’s versatility – you can even drive HDMI monitor with this PIO-based DVI code.

Continue reading “CAN Peripheral For RP2040, Courtesy Of PIO”