We’ve seen hackers run DOOM on a variety of appliances, from desk phones to pregnancy tests. Now, the final frontier has been conquered – we got DOOM to run on an x86 machine. Of course, making sure we utilize your PC hardware to its fullest, we have to forego an OS. Here are two ways you can run the classic shooter without the burden of gigabytes of bloated code in the background.

[nic3-14159] implemented this first version as a payload for coreboot, which is an open-source BIOS/UEFI replacement for x86 machines. Some might say it’s imperfect — it has no sound support, only works with PS/2 keyboards, and exiting the game makes your computer freeze. However, it’s playable, and it fits into your BIOS flash chip.

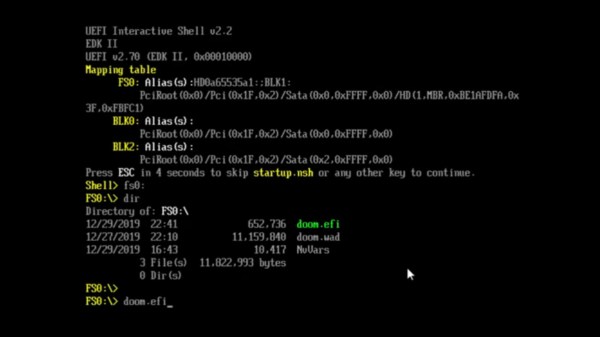

But what if your computer hasn’t yet been blessed with a free BIOS replacement? You might like this UEFI module DOOM port instead, originally made by [Warfish] and then built upon by [Cacodemon345]. To play this, you only need to compile the binary and an UEFI shell, then use the “Load EFI Shell” option in your UEFI menu – something that’s widely encountered nowadays. This version also lacks sound, but is a bit more fully featured due to all the facilities that UEFI provides for its payloads.

Of course there’s far more efficient ways to slay demons on your computer, but even if they aren’t necessarily practical from a gaming standpoint, these two projects serve as decent examples of Coreboot and UEFI payloads. BIOS replacements like coreboot take up so little space, we’ve even seen Windows 3.1 fit alongside coreboot in the BIOS chip. Wondering what UEFI is, even? Here’s a primer for you. And, if you don’t mind the exceptional bloat of a stripped-down Linux install, here’s a Linux image built from the ground up to run DOOM specifically.

Continue reading “DOOM? In Your BIOS? More Likely Than You Think!”