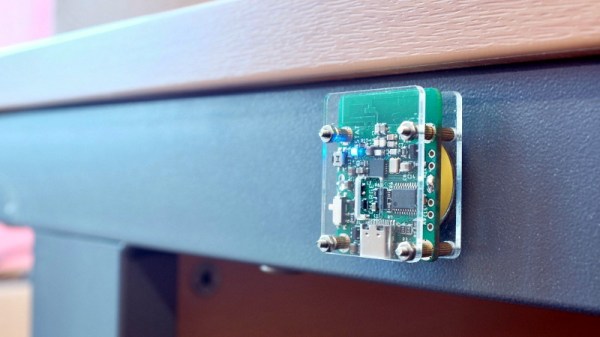

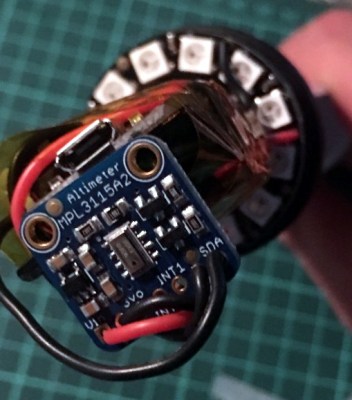

For his entry into the 2019 Hackaday Prize, [Tobius Daichi] is working on adding some motion control capabilities to everyone’s favorite Linux SBC. His 3+Pi board attaches to the Raspberry Pi’s GPIO header and gives you a convenient way to control four individual stepper motors. Perfect for a 3D printer, laser cutter, CNC, or anything else you can think of that needs to move in a few dimensions.

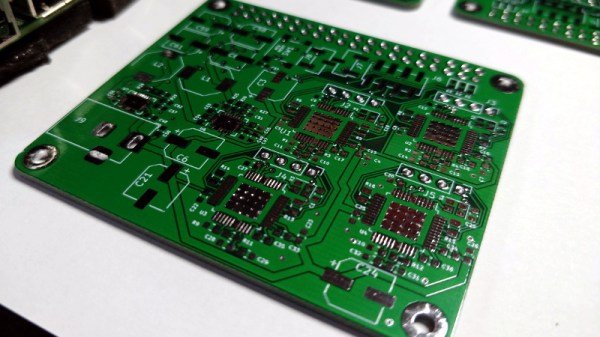

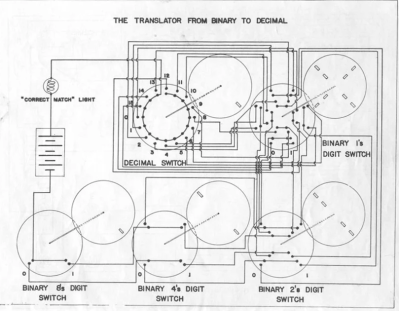

But such a simplistic description of the 3+Pi might be underselling it a bit. While [Tobius] says he was inspired by the classic Arduino CNC Shield that powers countless DIY 3D printers, he’s managed to improve on the concept. Rather than having the host Pi communicate directly with the stepper drivers, the 3+Pi features an onboard STM32F302CBT6 that handles the actual motor control. The Pi just needs to tell it what to do over UART.

If you’re looking to do things in real-time, having an onboard microcontroller handle the low-level aspects of talking to the stepper drivers can be a big help. A natural extension for this board could be support for the Klipper firmware, which leverages the fact that the Raspberry Pi is many times more powerful than your average 3D printer control board. With the Pi handling the math and providing the microcontroller instructions, Klipper allows for faster and more accurate printing than the microcontroller alone could accomplish.

If you’re looking to do things in real-time, having an onboard microcontroller handle the low-level aspects of talking to the stepper drivers can be a big help. A natural extension for this board could be support for the Klipper firmware, which leverages the fact that the Raspberry Pi is many times more powerful than your average 3D printer control board. With the Pi handling the math and providing the microcontroller instructions, Klipper allows for faster and more accurate printing than the microcontroller alone could accomplish.

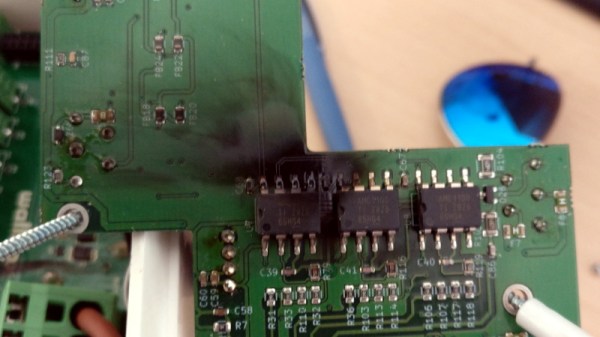

As for the stepper drivers themselves, [Tobius] has decided to go with the Trinamic TMC2041-LA-T. This chip is notable as it puts dual drivers in one 48-QFN package, which is great if you’re looking to save space on your board. Some might complain that the 3+Pi doesn’t allow for easily swapping out the stepper drivers if you manage to cook one like on the Arduino CNC shield, but realistically you could say the same about many purpose-built stepper control boards.

[Tobius] is tackling this project by himself currently, but does mention that he’s open to teaming up with anyone who’s got an interest in this sort of thing. There have been previous attempts at creating Linux-powered 3D printer controllers in the past, but we think this approach holds particular promise if for no other reason than the Raspberry Pi’s popularity.