The wildfires in California are now officially the largest the state has ever seen. Over 50,000 people have been displaced from their homes, hundreds are missing, and the cost in property damage will surely be measured in the billions of dollars when all is said and done. With a disaster of this scale just the immediate effects are difficult to conceptualize, to say nothing of the collateral damage.

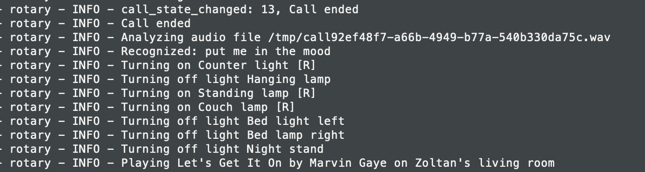

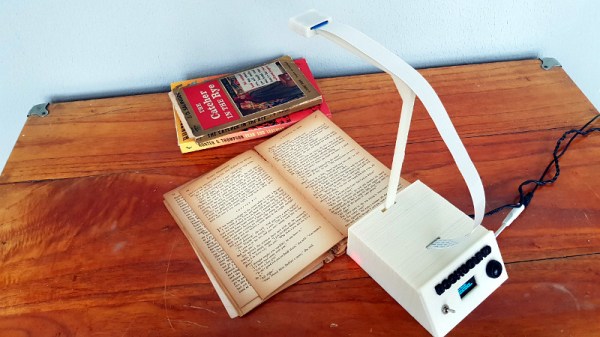

While not suggesting their situation is comparable to those who’ve lost their homes or families, Electric Imp CEO [Hugo Fiennes] has recently made a post on their blog calling attention to the air quality issues they’re seeing at their offices in Los Altos. To quantify the problem so that employees with respiratory issues would know the conditions before they came into work, they quickly hacked together a method for displaying particulate counts in their Slack server.

While not suggesting their situation is comparable to those who’ve lost their homes or families, Electric Imp CEO [Hugo Fiennes] has recently made a post on their blog calling attention to the air quality issues they’re seeing at their offices in Los Altos. To quantify the problem so that employees with respiratory issues would know the conditions before they came into work, they quickly hacked together a method for displaying particulate counts in their Slack server.

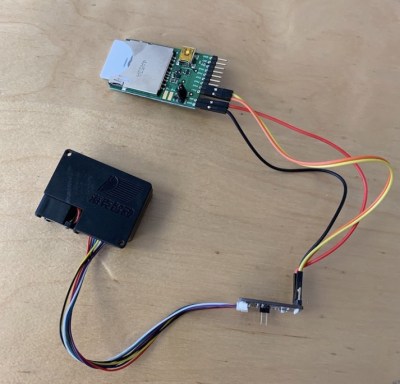

The key to the system is one of the laser particle sensors that we’re starting to see more of thanks to a fairly recent price drop on the technology. A small fan pulls air to be tested into the device, where a very sensitive optical sensor detects the light reflected by particles as they pass through the laser beam. The device reports not only how many particles are passing through it, but how large they are. The version of the sensor [Hugo] links to in his blog post includes an adapter board to make it easier to connect to your favorite microcontroller, but we’ve previously seen DIY builds which accomplish the same goal.

[Hugo] then goes on to provide firmware for the Electric Imp board that reads the current particulate counts from the sensor and creates a simple web page that can be viewed from anywhere in the world to see real-time conditions at the office. From there, this data can be plugged into a Slack webhook which will provide an instantaneous air quality reading anytime a user types “air” into the channel.

We’ve covered a number of air quality sensors over the years, and it doesn’t look like they’re going to become any less prevalent as time goes on. If anything, we’re seeing a trend towards networks of distributed pollution sensors so that citizens can collect their own data on their air they’re breathing.

[Thanks to DillonMCU for the tip.]