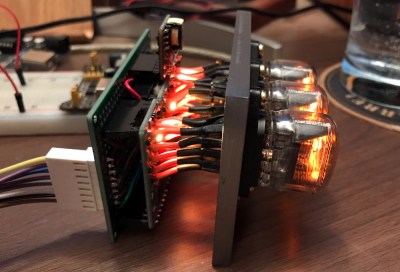

It took nearly a year for [Chris Crocker-White] to assemble this glorious mahogany and brass Geiger counter, but we think you’ll agree with us that it was time well spent. From the servo-actuated counter to the Nixie tubes and LED faux-decatrons, this project is an absolute love letter to antiquated methods of displaying information. Although for good measure, the internal Raspberry Pi also pushes all the collected radiation data into the cloud.

[Chris] says the design of this radiation monitor was influenced by his interest in steampunk and personal experience working on actual steam engines, but more specifically, he also drew inspiration from a counter built by [Richard Mudhar].

[Chris] says the design of this radiation monitor was influenced by his interest in steampunk and personal experience working on actual steam engines, but more specifically, he also drew inspiration from a counter built by [Richard Mudhar].

Based on a design published in Maplin back in 1987, [Richard] included a physical counter and LED “dekatron” displays as an homage to a 1960s era counter he’d used back in his school days. [Chris] put a modern spin on the electronics and added the glowing display of real-time Counts Per Minute (CPM) as an extra bonus; because who doesn’t like some Nixies in their steampunk?

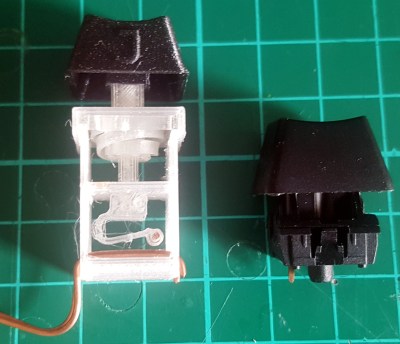

Internally, the pulses generated by a common Geiger counter board are picked up by some custom electronics to drive the servo and LEDs. Triggered by those same pulses, the Raspberry Pi 3A+ updates the Nixie display and pushes the data out to the cloud for analysis and graphing. Note that the J305β Geiger tube from the detector has been relocated to the outside of the machine, with two copper elbows used as connectors. This improves the sensitivity of the instrument, but perhaps even more importantly, looks awesome.

We’ve seen some very high-tech DIY radiation detection gear over the years, but these clever machines that add a bit of whimsy to the otherwise mildly terrifying process of ionizing radiation are always our favorite.

Continue reading “Steampunk Geiger Counter Is A Mix Of Art And Science”