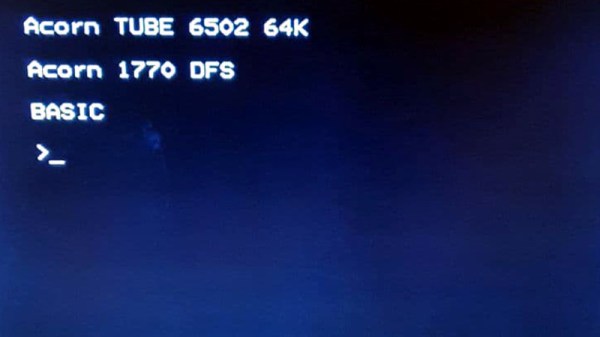

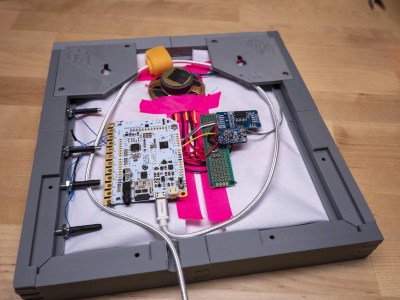

The Raspberry Pi is a fine machine that appears in many a retrocomputing project, but its custom Linux distribution lacks one thing. It boots into a GNU/Linux shell or a fully-featured desktop GUI rather than as proper computers should, to a BASIC interpreter. This vexed [Alan Pope], who yearned for his early days of ROM BASIC, so he set out to create a Raspberry Pi 400 that delivers the user straight to BASIC. What follows goes well beyond the Pi, as he takes something of a “State of the BASIC” look at the various available interpreters for the simple-to-code language. Almost every major flavour you could imagine has an interpreter, but as is a appropriate for a computer from Cambridge running an ARM processor, he opts for one that delivers BBC BASIC.

It would certainly be possible to write a bare-metal image that took the user straight to a native ARM BASIC interpreter, but instead he opts for the safer route of running the interpreter on top of a minimalist Linux image. Here he takes the unexpected step of using an Ubuntu distribution rather than Raspberry Pi OS, this is done through familiarity with its quirks. Eventually he settled upon a BBC BASIC interpreter that allowed him to do all the graphical tricks via the SDL library without a hint of X or a compositor, meaning that at last he had a Pi that boots to BASIC. Assuming that it’s an interpreter rather than an emulator it should be significantly faster than the original, but he doesn’t share that information with us.

This isn’t the first boot-to-BASIC machine we’ve shown you.

Header image: A real BBC Micro BASIC prompt. Thanks [Claire Osborne] for the picture.