The Playdate is an interesting gaming system. It’s a handheld, has a black and white screen, and superficially reminds us a little bit of the original Game Boy, right down to the button layout. But the fact that it has a second controller that pops out of the side, that this controller is a crank, and that the whole system was made by the same people that made Untitled Goose Game, makes us quite intrigued. Apparently it has made an impact on others, too, because this project turns the gaming system into a typewriter.

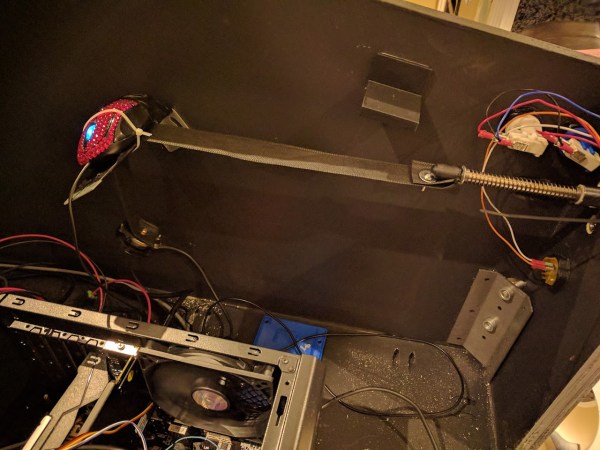

The Playdate doesn’t have native support for USB accessories unless it’s plugged into this custom 3D printed dock. Inside of the dock is a Teensy 4.1 which handles some translation between the keyboard and the console. Once the dock is taken care of the text editor needs to be side-loaded to the device as well. The word processor has the ability to move the cursor around, insert and delete text, and the project’s creator, [t0mg], plans to add more features in future versions like support for multiple files, changing the font, and a few other things as well.

For anyone interested in recreating this project, all of the printable files, the text editor, and the schematics are all available in the GitHub repo. It’s an impressive project for a less well-known console that we haven’t seen many other hacks for, unless you count this one-off Arduboy project which took some major inspiration from the Playdate’s crank controller.