Battery cells work by chemical reactions, and the fascinating Hybrid Microbial Fuel Cell design by [Josh Starnes] is no different. True, batteries don’t normally contain life, but the process coughs up useful electrons all the same; 1.7 V per cell in [Josh]’s design, to be precise. His proof of concept consists of eight cells in parallel, enough to give his cell phone a charge via a DC-DC boost converter. He says it’s not known how long this can be expected to last before the voltage drops to an unusable level, but it works!

There are two complementary sides to each cell in [Josh]’s design. On the cathode side are phytoplankton; green micro algae that absorb carbon dioxide and sunlight. On the anode side are bacteria that break organic material (like food waste) into nitrates, and expel carbon dioxide. Version 2 of the design will incorporate a semi-permeable membrane between the cells that would allow oxygen and carbon dioxide to be exchanged while keeping the populations of micro-organisms separate; this would make the biological processes more complementary.

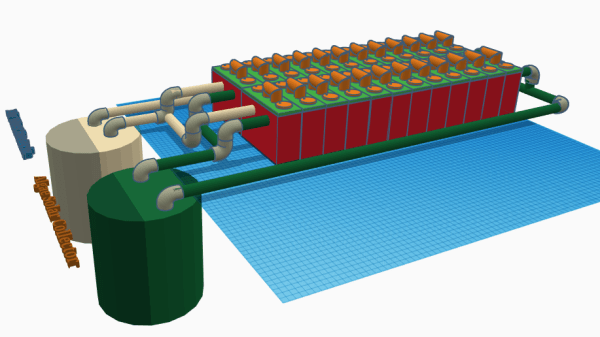

A battery consisting of 24 cells and a plumbing system to cycle and care for the algae and bacteria is the ultimate goal, and we hope [Josh] can get closer to that now that his project won a $1000 cash prize as one of the twenty finalists in the Power Harvesting Challenge portion of the Hackaday Prize. (Next up is the Human Computer Interface Challenge, just so you know.)