A while back, I bought a cheap spectrum analyser via AliExpress. I come from the age when a spectrum analyser was an extremely expensive item with a built-in CRT display, so there’s still a minor thrill to buying one for a few tens of dollars even if it’s obvious to all and sundry that the march of technology has brought within reach the previously unattainable. My AliExpress spectrum analyser is a clone of a design that first appeared in a German amateur radio magazine, and in my review at the time I found it to be worth the small outlay but a bit deaf and wide compared to its more expensive brethren. Continue reading “Perhaps It’s Time To Talk About All Those Fakes And Clones”

hardware1807 Articles

Bit-Banging Bidirectional Ethernet On A Pi Pico

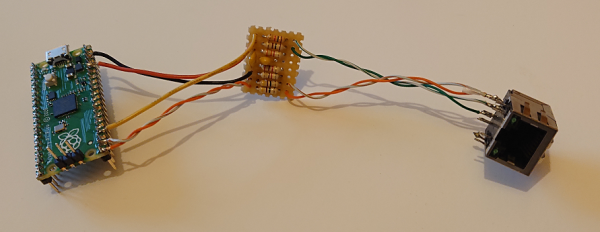

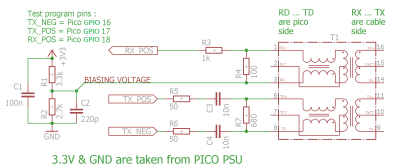

These days, even really cheap microcontroller boards have options that will give you Ethernet or WiFi access. But what if you have a Raspberry Pi Pico board and you really want to MacGyver yourself a network connection? You could do worse than check out this project by [holysnippet] that gives you a bit-banged bidirectional Ethernet port using only scrap passive components and software.

This project is similar to one we shared back in August by [kingyo], but differs in that what [holysnippet] has achieved is a fully-functional (albeit only around 7 Mbps) Ethernet port, rather than a simple UDP transmit device. The Ethernet connection itself is handled by the lwip stack. Connection to the RJ45 socket can be made from any of the Pi Pico pins, provided TX_NEG is followed directly by TX_POS, but the really hacky part is in the hardware.

Rather than developing hardware that would protect the Pico, this design admits that it “shamefully relies on the Pico’s input protection devices” to limit the Ethernet voltages to 3.3 V.

You’ll need an isolation transformer from some old Ethernet-enabled gear (either standalone or as part of a magnetic jack), but then it’s only resistors and capacitors from there. There are warnings not to connect this to PoE networks for obvious reasons, and the component layout needs to keep in mind the ~20 MHz frequencies involved, but to get this working at all feels like quite a feat.

Normally, there’d be no reason to go to these lengths, but it’s always educational to see if it can be done and, with the current component shortages, this is another trick to keep up your sleeve for emergencies!

Putting ports where they shouldn’t belong is not a new idea, of course. Back in the day we even shared an inadvisable ATTINY implementation of bit-banged Ethernet with no protection at all.

Thanks to [biemster] for the tip-off

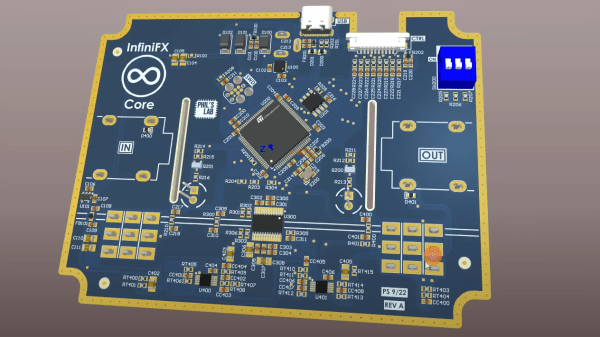

Aesthetic PCB Design Tips For Improved Functionality

Those of us hardware types that spend a lot of time designing PCBs will often look at other peoples’ designs with interest, and in some cases, considerable admiration. Some of their boards just look so good. But are aesthetics important? After all, for most products, the delicate electronic components on that PCB are tucked safely inside a protective enclosure. But, as [Phil’s Lab] explains, aesthetic PCB designs can lead to functional improvements, such that better-looking designs are also better performing, in terms of manufacturability (and therefore yield), electromagnetic compatibility (EMC), and several other factors that can be important.

First off, making a PCB easy to read and using sane placement of components and connections will speed up debugging by reducing errors. Keeping a consistent and not too-tight placement grid can give the pick and place machine an easier task, and reduce solder issues during reflow. But there are also more serious concerns, such as the enforcement of design partitionings — such as keeping analog circuits together and away from noisy power and digital areas — which can make the difference between functioning within specification, and failure.

The video goes into a few other interesting tips, one highlight is using a ground-tied PCB perimeter zone, with wavelength-of-interest via stitching. This will reduce EMC side emissions from the power plane, but also if you select an appropriate surface finish, and keep the solder mask open, you’ve got a free, full perimeter contact to ground your scope probe. Oh, and it looks good too.

Hackaday is no stranger to beautiful artistic PCBs, like the work of [Saar Drimer] and many others. But if one PCB doesn’t cut it for your needs, there’s always the ‘Oreo’ construction to consider.

Continue reading “Aesthetic PCB Design Tips For Improved Functionality”

TinyLlama Is A 486 In Your Pocket

We love retrocomputing and tiny computers here at Hackaday, so it’s always nice to see projects that combine the two. [Eivind]’s TinyLlama lets you play DOS games on a board that fits in your hand.

Using the 486 SOM from the 86Duino, the TinyLlama adds an integrated Crystal Semiconductor audio chip for AdLib and SoundBlaster support. If you populate the 40 PIN Raspberry Pi connector, you can also use a Pi Zero 2 to give the system MIDI capabilities when coupled with a GY-PCM5102 I²S DAC module.

Audio has been one of the trickier things to get running on these small 486s, so its nice to see a simple, integrated solution available. [Eivind] shows the machine running DOOM (in the video below the break) and starts up Monkey Island at the end. There is a breakout board for serial and PS/2 mouse/keyboard, but he says that USB peripherals work well if you don’t want to drag your Model M out of the closet.

Looking for more projects using the 86Duino? Checkout ISA Sound Cards on 86Duino or Using an 86Duino with a Graphics Card.

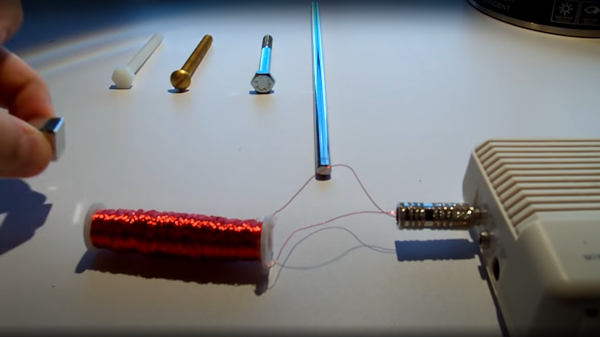

The Barkhausen Effect: Hearing Magnets Being Born

The Barkhausen effect — named after German Physicist Heinrich Barkhausen — is the term given to the noise output produced by a ferromagnetic material due to the change in size and orientation of its discrete magnetic domains under the influence of an external magnetic field. The domains are small: smaller than the microcrystalline grains that form the magnetic material, but larger than the atomic scale. Barkausen discovered that as a magnetic field was brought close to a ferrous material, the local magnetic field would flip around randomly, as the magnetic domains rearranged themselves into a minimum energy configuration and that this magnetic field noise could be sensed with an appropriately arranged pickup coil and an amplifier. In the short demonstration video below, this Barkhausen noise can be fed into an audio amplifier, producing a very illustrative example of the effect.

One example of practical use for this effect is with non-destructive testing and qualification of magnetic structures which may be subject to damage in use, such as in the nuclear industry. Crystalline discontinuities or impurities within a part under examination result in increased localized mechanical stresses, which could result in unexpected failure. The Barkhausen noise effect can be easily leveraged to detect such discontinuities and give the evaluator a sense of the condition of the part in question. All in all, a useful technique to know about!

If you were thinking that the Barkhausen is a familiar name, you may well be thinking about the Barkhausen stability criterion, which is fundamental to describing some of the conditions necessary for a linear feedback circuit to oscillate. We’ve covered such circuits before, such as this dive into bridge oscillators.

Continue reading “The Barkhausen Effect: Hearing Magnets Being Born”

Portable Monitor Extension For Nintendo Switch

Handheld consoles are always a tradeoff between portability and screen real estate. [Pavlo Khmel] felt that the Nintendo Switch erred too much on the side of portability, and built an extension to embiggen his Switch. (YouTube)

[Khmel] repurposed a Dell XPS 12 LCD panel for the heart of this hack and attached it to an LCD controller board to serve as an external monitor for the Switch. A 3D printed enclosure envelops the screen and also contains a battery, speakers, and a dock for the console. Along the top edges, metal rails let you slide in the official Joy-Cons or any number of third party controllers, even those that require a power connection from the Switch.

Since the Switch sees this as being docked, it allows the console to run faster and at higher resolution than if it were in handheld mode. The extension lasts about 5 hours on battery power, and the Switch inside will still be fully charged if you don’t mind being constrained to its small screen while you charge it’s bigger-screened exoskeleton.

Need more portable goodness? Be sure to check out our other handheld and Nintendo Switch hacks.

Continue reading “Portable Monitor Extension For Nintendo Switch”

First Folding IPhone Doesn’t Come From Apple

Folding phones are all the rage these days, with many of the major smartphone manufacturer’s having something in this form factor. Apple has been conspicuously absent in this market segment, so [KJMX] decided to take matters into their own hands with the “iPhone V.” (YouTube – Chinese w/subtitles via MacRumors).

Instead of trying to interface an existing folding phone’s screen with the iPhone, these makers delaminated an actual iPhone X screen to use in the mod. It took 37 attempts before they had a screen with layers that properly separated to be both flexible and functional. Several different folding phones were disassembled, and [KJMX] found a Motorola Razr folding mechanism would work best with the iPhone X screen. Unfortunately, since the iPhone screen isn’t designed to fold, it still will fail after a relatively small number of folds.

Other sacrifices were made, like the removal of the Taptic Engine and a smaller battery to fit everything into the desired form factor. The “iPhone V” boasts the worst battery life of any iPhone to date. After nearly a year of work though, [KJMX] can truly claim to have made what Apple hasn’t.

Curious about other hacks to let an iPhone do more than Apple intended? Check out how to add USB-C to an iPhone, try to charge it faster, or give one a big memory upgrade.