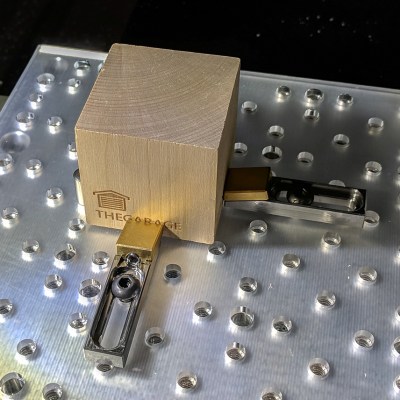

[Kevin] owns a benchtop CNC mill that has proven itself to be a capable tool, but after becoming familiar with some of its shortcomings, he has made a few modifications. In order to more efficiently hold and access workpieces on his custom fixturing table, he designed and made his own toe clamps and they look beautiful.

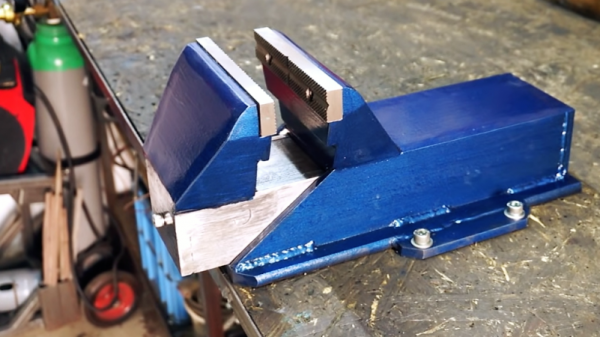

The usual way to secure a piece of stock to a fixturing table is to use top-down clamps, which hold the workpiece from the top and screw down into the table. However, this method limits how much of the stock can be accessed by the cutting tool, because the clamps are in the way. The most common way around this is to mount a vise to the table and clamp the workpiece in that. This leaves the top surface completely accessible. Unfortunately, [Kevin]’s benchtop Roland MDX-450 has a limited work area and he simply couldn’t spare the room. His solution was toe clamps, which screw down to the table and have little tabs that move inwards and downward. The tabs do the work of clamping and securing a piece of stock while maintaining a very low profile themselves.

The usual way to secure a piece of stock to a fixturing table is to use top-down clamps, which hold the workpiece from the top and screw down into the table. However, this method limits how much of the stock can be accessed by the cutting tool, because the clamps are in the way. The most common way around this is to mount a vise to the table and clamp the workpiece in that. This leaves the top surface completely accessible. Unfortunately, [Kevin]’s benchtop Roland MDX-450 has a limited work area and he simply couldn’t spare the room. His solution was toe clamps, which screw down to the table and have little tabs that move inwards and downward. The tabs do the work of clamping and securing a piece of stock while maintaining a very low profile themselves.

The clamp bases are machined from stainless steel and the heads are brass, and the interface between the two is a set screw. Inserting a hex wrench and turning the screw moves the head forward or back, allowing a workpiece to be clamped from the sides with minimal interference. His design was done in Fusion 360 and is shared online.

Another option for when simple clamps won’t do the job is a trick from [NYC CNC], which is to use an unexpected harmony of blue painter’s tape and superglue which yields great results in the right circumstances.