Drone racing comes in different shapes and sizes, and some multirotor racers can be very small indeed. Racing means having gates to fly though, and here’s a clever DIY design by [Qgel] that uses a small 3D printed part and a segment of printer filament as the components for small-scale drone racing gates.

The base is 3D printed as a single piece and is not fussy about tolerances, meanwhile the gate itself is formed from a segment of printer filament. Size is easily adjusted, they disassemble readily, are cheap to produce, and take up very little space. In short, perfect for its intended purpose.

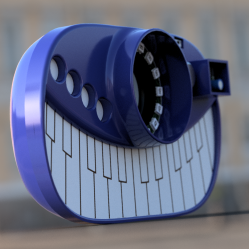

Races benefit from being able to measure lap time, and that led to DIY drone racing transponders, complete with a desktop client for managing the data. Not all flying is about racing, but pilots with racing skills were key to getting results in this Star Wars fan film that used drones. Finally, those who still feel that using the word “drone” to include even palm-sized racers is too broad of a use may be interested in [Brian Benchoff]’s research into the surprisingly long history of the word “drone” and its historically broad definition.

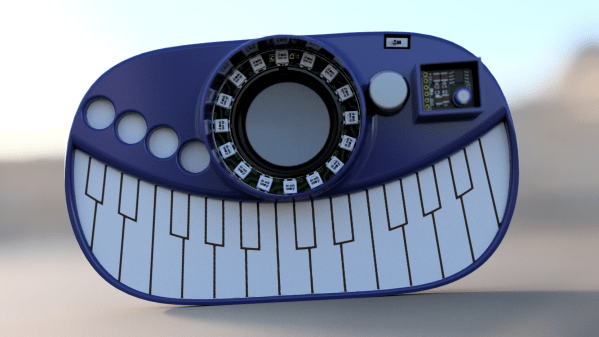

The unit’s stylus and PCB key interface resemble a

The unit’s stylus and PCB key interface resemble a