Believe it or not, there was a time when the only way for many of us to play video games was to grab a roll of quarters and head to the mall. Even though there’s a working computer or video game console in essentially every house now doesn’t mean we don’t look back with a certain nostalgia on those times, though. Some have turned to restoring vintage arcade cabinets and others build their own. This hackerspace got a unique request for a full-sized arcade cabinet that was also easily portable as well.

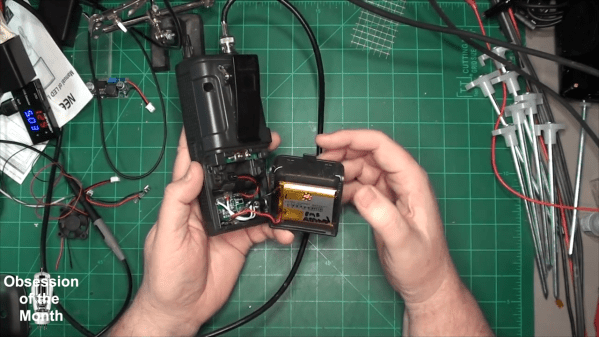

The original request was for a portable arcade cabinet, and the original designs were for a laptop-like tabletop arcade. But further back-and-forth made it clear they wanted full-size cabinets that just happened to also be portable. So with that criteria in mind the group started building the units. The updated design is modular, allowing the controls, monitor, and Raspberry Pi running the machines to be in self-contained units, with the cabinets in two parts that can quickly be assembled on-site. The base is separate and optional, with the top section capable of being assembled on the base or on something like a tabletop or bar, and the electronics section quickly drops in.

While the idea of a Pi-powered arcade cabinet is certainly nothing new, the quick build, prototyping, design, and final product that’s mobile and quickly assembled are all worth checking out. There is even more information on the build at the project’s GitHub page including Fusion 360 models. If you need your cabinets to be even more portable, this tabletop MAME cabinet is a great place to start.