Join us on Wednesday, July 21 at noon Pacific for the Python Your Keyboard Hack Chat with the Adafruit crew!

Especially over the last year and a half, most of us have gotten the feeling that there’s precious little distinction between our computers and ourselves. We seem welded together, inseparable even, attached as we are day and night to our machines as work life and home life blend into one gray, featureless landscape where time passes unmarked except by the accumulation of food wrappers and drink cans around our work areas. Or maybe it just seems that way.

Regardless, there actually is a fine line between machine and operator, and in most instances it’s that electromechanical accessory that we all love to hate: the keyboard. If you buy off the shelf, it’s never quite right — too clicky, not clicky enough, wrong spacing, bad ergonomics, or just plain ugly design. The only real way around these limitations is to join the DIY keyboard crowd and roll your own, specifically customized to your fingers and your needs — at least until you realize that it’s not quite perfect, and need to modify it again.

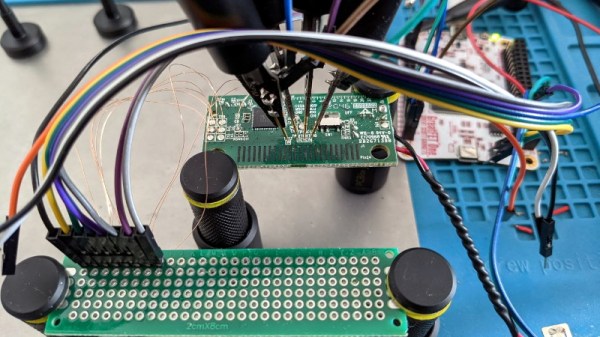

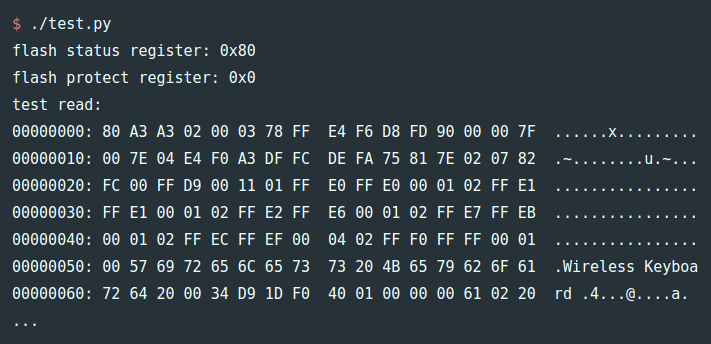

Hitting this moving target is often as much a software problem as it is a hardware issue, but as is increasingly the case these days, Python is ready to help. To go into depth on how Python can be leveraged for the custom keyboard builder, our good friends at Adafruit, including Limor “Ladyada” Fried, Phillip Torrone, Dan Halbert, Kattni Rembor, and Scott Shawcroft will stop by the Hack Chat. We suspect they’ll have some cool stuff to show off, in addition to sharing their tips and tricks for making DIY keyboards just right. If you’re building custom keebs, or even if you’re just “keyboard curious”, you won’t want to miss this one.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, July 21 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.

Our Hack Chats are live community events in the Hackaday.io Hack Chat group messaging. This week we’ll be sitting down on Wednesday, July 21 at 12:00 PM Pacific time. If time zones have you tied up, we have a handy time zone converter.