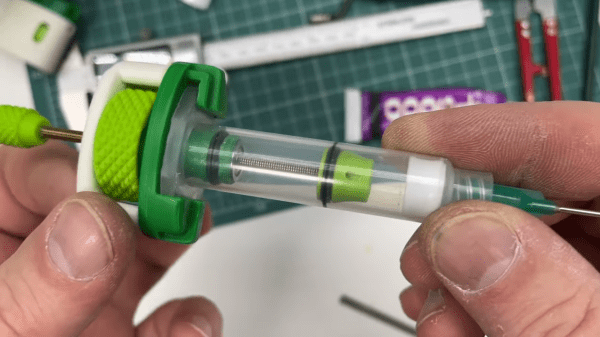

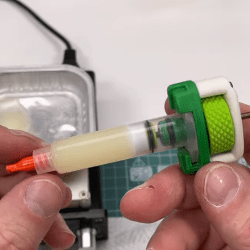

[Perinski]’s design for a mechanical flux dispenser uses some common hardware and a few 3D printed parts to create a syringe with fine control over just how much of the thick stuff gets deposited. The design is slick, and there’s a full parts list to accompany the printed pieces. [Perinski] even has some useful tips on how to most effectively get flux into 5 mL syringes without making a mess, which is a welcome bit of advice.

There is also a separate companion design for a magnetic syringe cap. Not only does it have an O-ring to keep things sealed and clean, but the tip of the cap has a magnet embedded into it, so that it can be stowed somewhere safe while the dispenser is in use, and doesn’t clutter the workspace.

There is also a separate companion design for a magnetic syringe cap. Not only does it have an O-ring to keep things sealed and clean, but the tip of the cap has a magnet embedded into it, so that it can be stowed somewhere safe while the dispenser is in use, and doesn’t clutter the workspace.

This is all a very interesting departure from the design of most syringe dispensers for goopy materials, which tend to depend on some kind of pneumatic action. Even so, we’ve also seen that it’s possible to have a compact DIY pneumatic dispenser that doesn’t require a bulky compressor.

If you can’t quite figure out how the ergonomics of [Perinski]’s design are intended to work one-handed, you’re not alone. One holds the syringe in their hand, and turns the large dial in small increments with a thumb to control extrusion. [Perinski] demonstrates it close-up around the 4:50 mark, but if you have a few minutes it is worth watching the entire video, embedded below.

Continue reading “DIY Mechanical Flux Dispenser Syringe Has Fine Control”