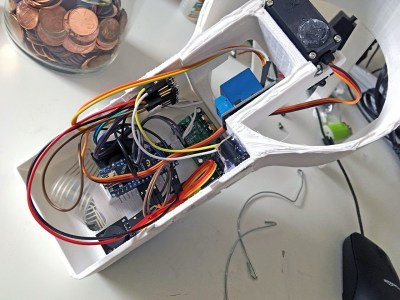

Over the years, we’ve seen numerous projects that attempted to 3D print speaker enclosures that deliver not only a bit of custom flair, but hopefully halfway decent sound. Though as you’d probably expect, the drivers themselves are always standard run-of-the mill hardware mounted into the plastic enclosure. But given the research being conducted by [Paul Ellis], that might not be a safe assumption for much longer.

His quest to develop a full-range 3D speaker has taken him through several design revisions over the last two years, with each one being put through testing procedure that compared its frequency response to “real” speakers from manufacturers like Dayton and Bose. The project is very much ongoing, but a recently completed iteration of the driver design managed to exceed 80 dB at 1 W. In terms of audio quality, [Paul] reports they can hold their own against commercially available drivers. You can hear for yourself in the video after the break.

His quest to develop a full-range 3D speaker has taken him through several design revisions over the last two years, with each one being put through testing procedure that compared its frequency response to “real” speakers from manufacturers like Dayton and Bose. The project is very much ongoing, but a recently completed iteration of the driver design managed to exceed 80 dB at 1 W. In terms of audio quality, [Paul] reports they can hold their own against commercially available drivers. You can hear for yourself in the video after the break.

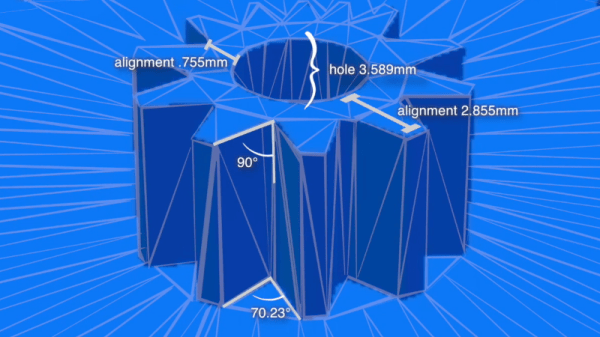

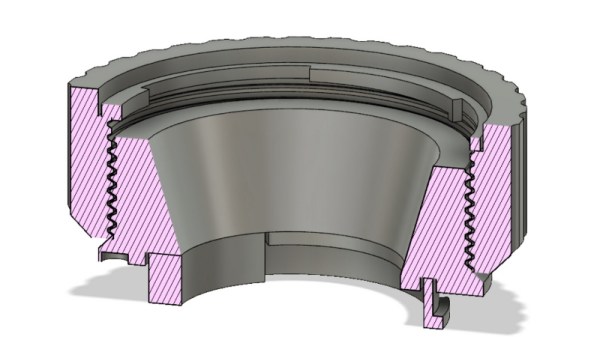

Ultimately, he hopes to be able to sell his 3D printed speakers in kit form to anyone who’s looking for the last word in bespoke audio hardware. The idea being that the drivers and enclosure will be completely modular, allowing the user to swap out individual components for ones printed (or not) in different materials so they can tune the in-person sound to their exact specifications. To facilitate this rapid reconfiguring of the drivers, the designs use some neat tricks like having the magnets be removable rather than glued in so they could be swapped out non-destructively.

This isn’t the first fully 3D printed speaker driver we’ve ever seen, Formlabs showed one off that was made on their SLA printer back in 2015, and we actually saw a rudimentary take on the same idea earlier this year. But the work that [Paul] has done here is certainly the most thorough, and dare we say practical, take we’ve ever seen on the concept.

Continue reading “Putting 3D Printed Speaker Drivers To The Test”