The regular Hackaday reader no longer needs to be reminded about how popular the ESP8266 is; they see the evidence of that several times a day. But what might not be quite so obvious is that it isn’t just us hacker types that are in love with the inexpensive IoT microcontroller, it’s also popping up more and more frequently in commercial products.

As [Majenko] demonstrates, one of those ESP-powered devices is the LOHAS Smart LED Bulb. Upon cracking one open, he found that these relatively low-cost bulbs are little more than a standard ESP8266 chip and a couple of LED drivers. He wanted to see how hard it would be to get his own code running on the bulb, and by the looks of it, it took longer to get the thing open then it did to load it up with a custom firmware.

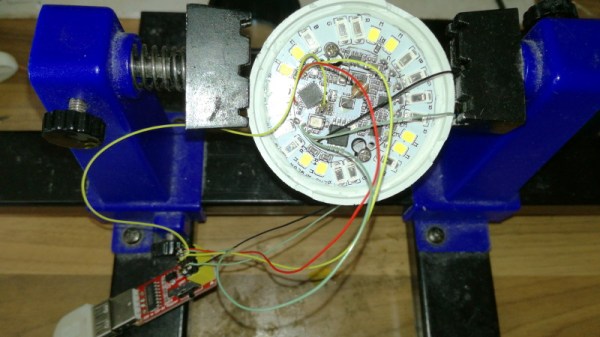

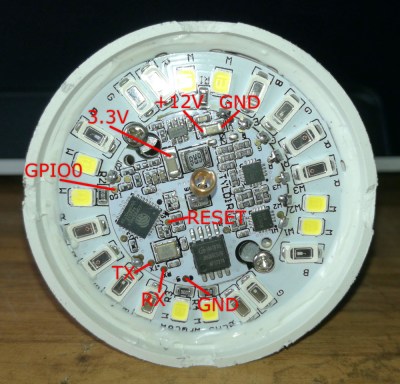

The bulb’s PCB features the aforementioned ESP8266, a 1MB 25Q80 flash chip, and MY9231 LED drivers. Whoever put the board together was nice enough to label the RX, TX, and GPIO test points, though [Majenko] notes that what’s labeled as 3.3 V appears dead. With a ESP-01 programmer wired up to the board and the appropriate board settings (which he provides), you can use the Arduino IDE to upload whatever you like to it.

The bulb’s PCB features the aforementioned ESP8266, a 1MB 25Q80 flash chip, and MY9231 LED drivers. Whoever put the board together was nice enough to label the RX, TX, and GPIO test points, though [Majenko] notes that what’s labeled as 3.3 V appears dead. With a ESP-01 programmer wired up to the board and the appropriate board settings (which he provides), you can use the Arduino IDE to upload whatever you like to it.

Running “Hello World” on a smart bulb is fun and all, but what about kicking on those LEDs? [Majenko] found a library that works with the MY9231 drivers, and it didn’t take long to figure out which of the ESP’s pins were used to communicate with them. All in all, he said it was far easier than he expected.

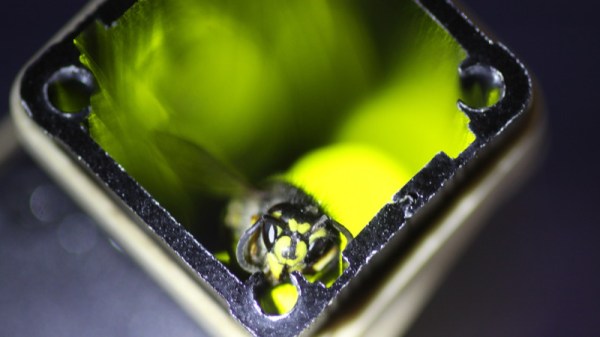

You’ll probably want to put this bulb back into service after reprogramming, so [Majenko] advises caution when cracking open the shell. There are clips holding on the diffuser which he assures us are going to break no matter what you do, plus some silicone adhesive. He suggests super glue to hold it together when you’re done programming it, and using an OTA firmware so you don’t need to get back in there.

In the past we’ve shown how some hackers are rolling their own smart bulb hardware, but with cheap commercial offerings that are so easily hackable, it frankly doesn’t seem worth the effort. On the other hand, an influx of cheap ESP-powered bulbs isn’t all good news.