[Gijs Gieskes] has a long history of producing electronic art and sound contraptions, and his Zonneliedjes (sunsongs) project is certainly an entertaining perpetuation of his sonic creations. With the stated goal of making music from sunlight, the sunsongs most prominent feature is solar panels.

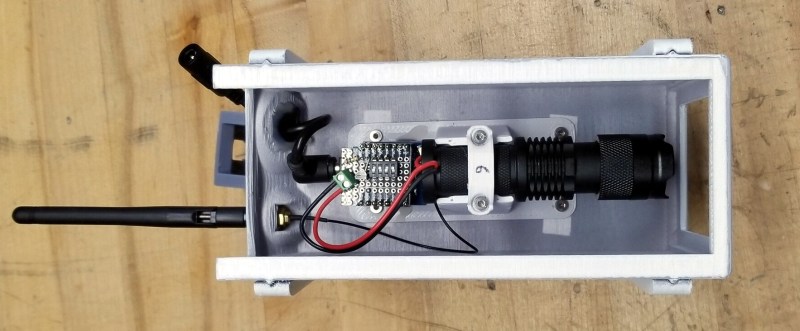

Although It’s not clear how the photons transform into the rhythmic crashes and random beep-boop sounds, the results are quite satisfying. We have a strong suspicion that the same principals that turn random junk into BEAM robots are at work, maybe with some circuit bending sprinkled on for good measure. One detail we were able to glean from a picture of the device he calls “mobile” was a 40106 oscillator, which [Gijs] has used in previous projects.

The construction style that [Gijs] uses reminds us of the “Manhattan” construction style the amateur radio homebrewing community favors. Squares of copper PCB are glued directly to the back of the solar cells and the circuits are built atop them. Looking carefully at the pictures we can also see what look like cutoff leads, suggesting a healthy amount of experimentation to get the desired results, which we can all relate to.

Be sure to check out the video after the break, and also [Gijs] website. He’s been hacking away at projects such as these for a very long time, and we’ve even featured his projects going back more than 15 years. Thanks for the continued hacks, [Gijs]. We look forward to seeing what you come up with next!

If the terms “BEAM robotics” and “circuit bending” are unfamiliar to your ears (or if a refresh is due), be sure to check out our recent re-introduction to BEAM robotics and our classic “Intro to Circuit Bending” to get acquainted. Continue reading “Spiffy Summer Project Sources Solar Sounds From Scraps”