We can certainly relate to an incomplete project sowing the seed for a better one, and that’s just what happened in [JohnnyQ90]’s latest video. He initially set out to create an air compressor powered by a nitro engine, and partially succeeded – air was compressed, but not nearly enough to be useful.

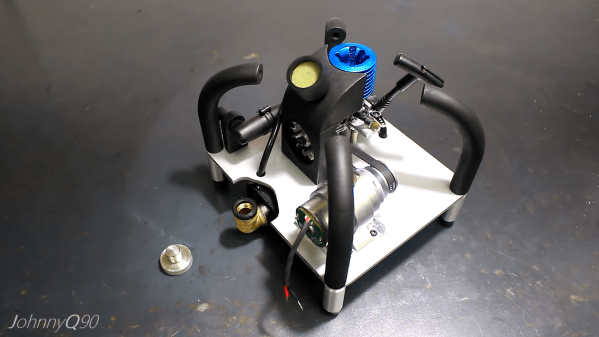

Instead, he changed tack and decided to use the 1 cc engine to make a small electric generator. [JohnnyQ90] is, of course, no stranger to the nitro engine, having previously brought us the micro chainsaw conversion, and nitro powered rotary tool. This time round, the build is a conceptually simple task: connect an engine to a DC motor and you’re done. But physically implementing it in an elegant way is a different story, and this is always where [JohnnyQ90] shines; we never get tired of watching him produce precision parts on the lathe. A fuel tank is made from a modified Zippo can and, courtesy of a CNC milled fan and 3D printed shroud, the motor air cools itself.

[JohnnyQ90] is, of course, no stranger to the nitro engine, having previously brought us the micro chainsaw conversion, and nitro powered rotary tool. This time round, the build is a conceptually simple task: connect an engine to a DC motor and you’re done. But physically implementing it in an elegant way is a different story, and this is always where [JohnnyQ90] shines; we never get tired of watching him produce precision parts on the lathe. A fuel tank is made from a modified Zippo can and, courtesy of a CNC milled fan and 3D printed shroud, the motor air cools itself.

Towards the end of the video, [JohnnyQ90] plays with the throttle a little, causing the bulb connected to the generator to brighten accordingly. It might be fun to control the throttle with a servo and try to regulate the voltage on the output under different load conditions.

We love novel ways of creating electricity; previously we’ve written about how to generate power from a coke can, as well as this 120 W thermoelectric generator (TEG) setup.

Continue reading “Out Of Batteries For Your Torch? Just Use A Mini Nitro Engine”