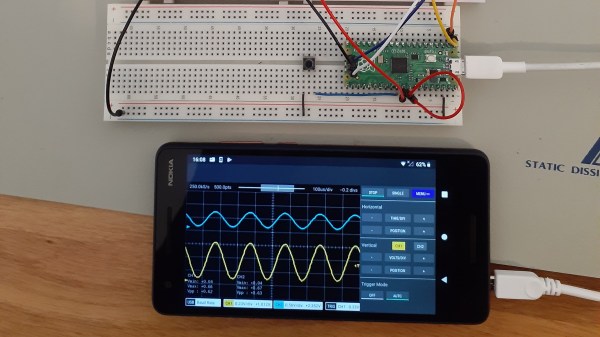

Adding an audio channel to your microcontroller project can mean a pile of extra components and a ton of processing power, as a compressed stream must be retrieved and sent to a dedicated DAC. Or if you are [rdpoor], it can mean hooking up a low-pass filter to the UART that’s present on even the simplest of devices, and constructing a serial data stream that mimics PWM audio.

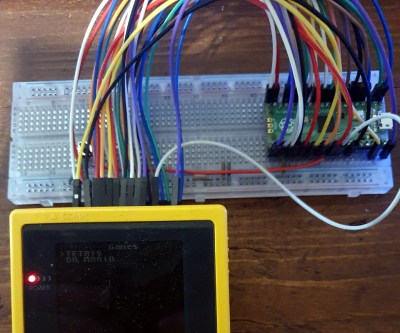

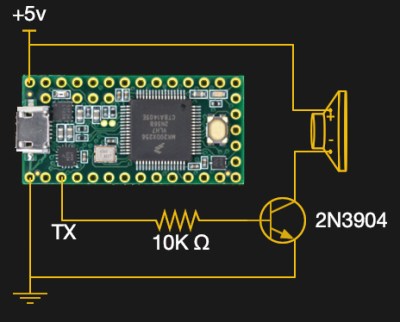

WART is a Python script that converts a WAV file into a C formatted byte array that can be baked into your microcontroller code, and for which playback is as simple as streaming it to the UART. The example uses a Teensy and a transistor to drive a small speaker, we’re guessing that better quality might come with using a dedicated low-pass filter rather than relying on the speaker itself, but at least audio doesn’t come any simpler.

The code can be found in a GitHub repository and there’s a few recordings of the output in the files section Hackaday.io page, one is embedded below. It’s better than we might have expected given that the quality won’t be the best at the PWM data rate of even the fastest UART. But even if you won’t be incorporating it into your music system any time soon we can see it being a useful addition for such things as small warning sounds. Meanwhile if persuading serially driven speakers to talk is of interest, there’s always the venerable PC speaker.

Continue reading “Digital Audio For Microcontrollers Doesn’t Come Much Simpler Than A WART”