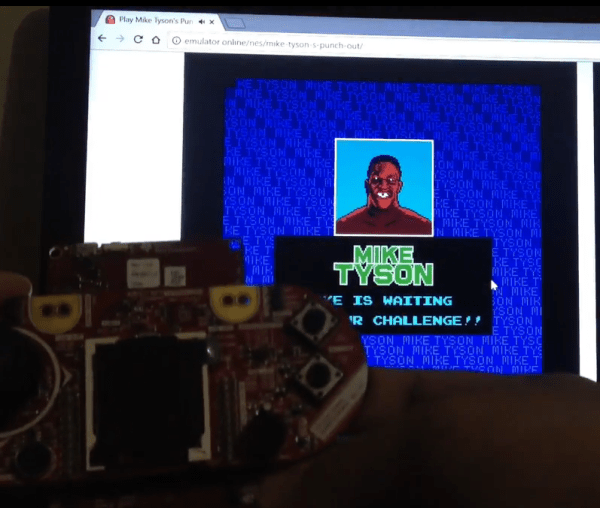

For several years now, a more energy-efficient version of Bluetooth has been available for use in certain wireless applications, although it hasn’t always been straightforward to use. Luckily now there’s a development platform for Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) from Texas Instruments that makes using this protocol much easier, as [Markel] demonstrates with a homebrew video game controller.

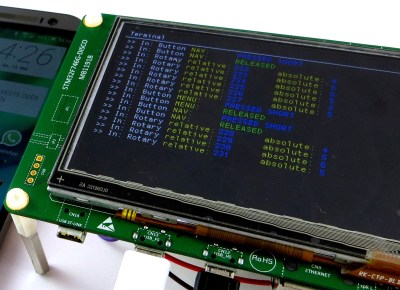

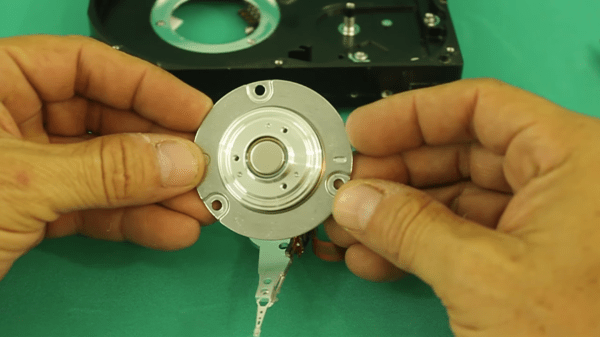

The core of the project is of course the TI Launchpad with the BLE package, which uses a 32-bit ARM microcontroller running at 48 MHz. For this project, [Markel] also uses an Educational BoosterPack MKII, another TI device which resembles an NES controller. To get everything set up, though, he does have to do some hardware modifications to get everything to work properly but in the end he has a functioning wireless video game controller that can run for an incredibly long time on just four AA batteries.

If you’re building a retro gaming console, this isn’t too bad a product to get your system off the ground using modern technology disguised as an 8-bit-era controller. If you need some inspiration beyond the design of the controller, though, we have lots of examples to explore.

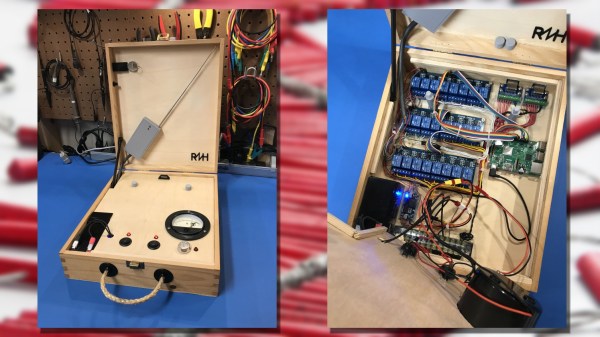

[netmagi] claims his yearly display is a modest affair, but this controller can address 24 channels, which would be a pretty big show in any neighborhood. Living inside an old wine box is a Raspberry Pi 3B+ and three 8-channel relay boards. Half of the relays are connected directly to breakouts on the end of a long wire that connect to the electric matches used to trigger the fireworks, while the rest of the contacts are connected to a wireless controller. The front panel sports a key switch for safety and a retro analog meter for keeping tabs on the sealed lead-acid battery that powers everything. [netmagi] even set the Pi up with WiFi so he can trigger the show from his phone, letting him watch the wonder unfold overhead. A few test shots are shown in the video below.

[netmagi] claims his yearly display is a modest affair, but this controller can address 24 channels, which would be a pretty big show in any neighborhood. Living inside an old wine box is a Raspberry Pi 3B+ and three 8-channel relay boards. Half of the relays are connected directly to breakouts on the end of a long wire that connect to the electric matches used to trigger the fireworks, while the rest of the contacts are connected to a wireless controller. The front panel sports a key switch for safety and a retro analog meter for keeping tabs on the sealed lead-acid battery that powers everything. [netmagi] even set the Pi up with WiFi so he can trigger the show from his phone, letting him watch the wonder unfold overhead. A few test shots are shown in the video below.